She’s Hard to Live With

By Casey Arthur

It was cold. Damn cold. The stench of the summer humidity had finally flown south and was all but replaced with a crispy winter brisk wind. Many believe December 25th to be Christmas but for a waterfowler, these are the nights that feel more like it. Something different, everything alive and electric. Local lodging teeming with scores of hunters full of hope that their next morning’s outing will be as fruitful as these conditions have proven in the past. Gas stations full with a line gushing into traffic, flashlights and headlamps shining into back seats trying to arrange last minute gear conundrums, and firepits blazing in each seasonal rental yard offering heat that this front surely wouldn’t provide.

There I was, driving through it. I’m excited. These storms come in once a year if luck strikes but if you truly looked into it, probably more like once every two years proves a safer assumption. I felt like I was in a parade with everyone looking to see who was driving through. It’s very hard to describe, but in that moment, being from the area, knowing where the ducks are, and pretty well knowing how the next morning is going to go, you feel like the only one who knows the secret.

Pulling up to the homeplace where I grew up even had a different feel to it. The fever for getting on the sound and watching birds fly was flowing through me like malaria. My parents knew it too. Everything was in place and supper was on the table. It was an occasion not to be taken lightly. My friends were set to hunt with me the next morning and were also staying there for the night and would be arriving soon. I wanted to show them a good time, the whole Core Sound experience. This not only meant frequently shouldering and mounting a gun but moreover, eating stewed ducks with rutabagas and dodgers, chewing on a perfectly cooked pecan or chocolate pie, and telling stories of past hunts until we were too tired to finish em’. Nothing left to do but put the boat over and make sure it was ready for the next morning. We did, and it was.

Everyone came back, found a comfy spot, and dozed off to sleep; except me. No one ever knew it, but I was awake most of the night tossing and turning. As luck would have it, the storm had actually drifted further south causing the temperature to drop even more and the winds to pick up slightly at a more favorable direction for the spot we were hunting. The adrenaline rush from this was like drinking a triple espresso shot and trying to use the coffee cup for a pillow. With everything locking up, our spot was going to be the best. We might have to break ice, but after that it would be the only place left for a wary bird to light. It was a storm, and we were the only place of refuge in the bay. Maybe I drifted off for ten minutes at the pinnacle of my forced relaxation, and I faintly remember a short dream about Blackheads in figure eight flight coming around and twitching to call the shot, but that was interrupted by the sound of my alarm. It was time.

Breakfast was already fixed and in bags. My parents really are the best hosts regardless of my biases. After a short conversation answering a question or two about a few random duck mounts on the walls and maybe a few more about some old decoys on shelves from my hometown, we were all out the door. When we all got out on the porch, we felt it. The coldest wind you’ll find in our area. Some even went back inside to pick up an extra layer. It was colder than expected and we all immediately began discourse about how the ducks would be moving. We headed immediately to the landing where the boat was already overboard and coated in ice.

A two-stroke Suzuki coming to life, one party member falling on the icy deck bringing laughter to cut the nervous tension, a quick check of the trucks to make sure we remembered everything, and a few sacks of hand-carved decoys, and we were off. The harbor was iced over but not too thick. It’s quite a feat to freeze salt water. There were stories from the roaring 20’s of the sound freezing over paving the way for rickety Model T’s to drive from one shore to another, over two and a half miles to the banks. Whether the tall tale is completely true or not, it had always occupied my thoughts while I gazed out over the sound. What good deeds had we done to deserve to live this historic moment? All of the hunters were huddled around in the boat trying to stave off the cold with their hands deep into their jacket pockets and even some turned around using their hoods to shield them from the wind. My eyes kept freezing over making the red and green navigation lights blurry like a drunken holiday. We were hollering like a group of pirates that just plundered a ship as we torched through the chop headed to our destination.

I nosed the boat up to the bush blind. It was just like I left it. I chuckled to myself as I hadn’t had the time to check on it lately and was surprised that the recent king tide had left it alone. All cargo was being removed from the boat while I made sure she stayed pinned to the shore. I started throwing decoys over from the stern. I noticed that the boat had built up more ice as the water was as freezing as we were busting waves and snowing on us. One sack of decoys over. I turned to the bow and noticed that most of the gear was off the boat. Two sacks of decoys over and set. Out of the corner of my eye I barely caught a glimpse of the first ducks flying into the bay. Three and four sacks of decoys over, floating upright, and spaced. I needed to hurry and put the boat up as shooting time was coming up quickly.

After getting the all clear from the boys on shore, I clicked the shift lever to “rewind” and backed the skiff off the shoreside. As I was pulling away, I told everyone to get their guns loaded and be on the lookout as legal time would surely be before I got back from hiding the boat from plain view several hundred yards up the shoreline. I shoved the boat in head-gear and the bow popped to attention before me. Gripping the helm, I cut the boat hard to starboard around the point hastily as to get out of the way for incoming ducks. At least the other boys would have a chance on the first birds although I’d be late to join them. As I kept cutting around, I noticed that it felt like the wind had picked up even more and the temperature seemed to have plummeted to new depths.

This extreme cold is hard on a boat, any boat really. These temperatures really complicate matters. It was no different for me. This is the point of the adventure that turns around on me. This is the moment that Core Sound was going to show me who was in charge. I came into the shoreside with the intention of nosing the bow to shore, stepping off with my anchor, and setting it. After all, the wind was blowing me directly offshore and wasn’t supposed to shift. This was perfect, as I could simply plant an anchor in the marsh and let the wind hold the boat off. A quick exit was exactly what I was planning so I could get to hunting. But plans can never be carved in stone on the sound. I grabbed the icy wheel and began to turn back to port about 30 yards away from my destination when I felt a snap.

The boat continued to careen to starboard regardless of my correction to the left, so I had no choice but to pull the throttle back and into neutral. Something was wrong, very wrong. As I tried to reason with the helm the wind was picking up even more. By the time I looked up from my reasoning, I was 100 yards offshore. I was headed for South Core Banks at a rapid clip. The wind was gusting to 40 knots and my gap from land was increasing by the second. The motor was frozen in place causing the boat to do endless circles. The harder the throttle, the tighter the circle. Useless circles. I laid down in the back of the boat and began kicking the motor yelling “Damn ye! Damn ye!” to try and get it to come around straight or to figure out any way to release the pressure from those damned iced over cables so I could manually steer even in a primitive fashion. It was no use. I was along for the ride and was no longer the Captain.

I stopped kicking the motor when I started to sweat. Though much younger and a little less wise, I knew that if I got soaking wet from sweat in this weather that would be the end of me. I went back to the console to keep figuring on a solution. Something kept telling me to not give up and that I could figure a way out of this. Finally, my brain thawed out when the lightbulb over my head turned on. I could throttle the boat enough where the bow would turn into the wind, then release the throttle and let the wind kick me back around. After all, sailors use this tactic to get where they want to go, and this seemed like my only way to make forward progress. So that’s what I did. I did this for maybe an hour and covered a very short distance, but it was enough distance to get me behind an island I was familiar with from hunting there when I was very young. I knew this terrain in my sleep which would prove very useful. Once some of the wind was cut off, I was able to travel faster and seemed to be making good time getting back to the mainland where I knew I could at least walk around the shore back to safety, a warm cup of coffee, and options of other boats to pick the hunters up with.

If my luck was running away from me like a carrot on a stick, this is the point where the line gets cut and the carrot falls overboard. My shifting cable, which had been my lifeline to this point and was causing my panic and fear for my life to fade, snapped in half. When I pushed the gear shift up the next time, nothing happened. My skiff was officially a lifeless barge. I don’t know where I learned this, but when you make a plan, always make a plan b. Once you make a plan b, have a plan c. If all of the plans seem to be failing, take that time to come up with a plan d and so forth and so on. I think at this point I might have been on plan z! Nevertheless, I had one.

I had chest waders on and Core Sound really isn’t that deep overall, so I could simply walk to the nearby island that I was so familiar with and wade across the shallow channel to the mainland. With this in mind, I immediately threw the anchor. The Danforth style anchor blades caught on a Core Sound grass bed and held. I tied it off to the front cleat and began to make my way over the gunnel to begin walking to shore. I kept dipping further and further into the sound and eventually water was coming in the top of my waders around my underarms. It was too deep! I had managed to anchor in one of the only spots this close to shore that was too deep to wade in. I worked hard to get my legs back up over the gunnels to get back in the skiff, but I couldn’t do it. I pulled myself to the back of the boat and got my feet up on the motor and finally was able to get back in the boat.

Exhausted, mentally drained, and starting to get really… really cold, I rolled into the deck of the boat. I stayed there the better part of 5 minutes, but it felt like 5 hours. I mustered up the energy to get up and decided to start over with a new set of solutions. I did have one anchor out but for some reason I didn’t think of my second anchor. Not two months earlier I had added a stern anchor with a fair length of chain and anchor rope.

That’s when it hit me; I can throw one anchor, pull the boat to it, then throw the other anchor before I lose my progress. If I throw these anchors one at a time and pull to them, I could eventually get close enough to shore that I could wade the rest of the way. One anchor thrown and tied off and the other anchor at my feet, I began to put my plan into motion. By this time, I was soaking wet with sweat, and I could feel the cold creeping in. With each pull of the frozen anchor rope I could feel my brittle gloves ripping and tearing and soon started to notice that the rope was rubbing my hands raw. This was not good news but if I just kept this plan going, I would soon be close enough.

I was too weak to throw the anchor anymore. My gloves ripped off of me and my energy levels completely dropped to nothing, I had to quit. With my body temperature steadily decreasing, I had to try to wade yet again. This time, I knew if I was unsuccessful, I might not have enough strength to get my legs back in the boat. It did take me quite some time to muster up enough courage to take the plunge. I knew if I took water in my waders that I would not survive the below freezing waters long enough to get to shore if I didn’t drown first. So, with that, I lowered the remaining anchor rope and checked it against my body.

The anchor rope was wet above my underarms but only a little bit. I knew it shallowed up quickly there; I also knew I couldn’t afford to hang out on the boat until someone figured that I was missing. I laid on the gunnel and launched my legs over the side holding on until I could ease myself down into the sound. I kept sinking and sinking. The water was up to my waist. My grip started to weaken and now the water was up to my chest. I felt a slight trickle of water come over the top of my waders. It was cold.

The kind of cold that you instantly knew to respect. The deadly kind of cold. Just when I was starting to give up hope that I had pulled myself close enough to shore, my feet both touched bottom. It was sandy, I could tell. More good news as a muddy bottom might have been my final destination. As I began walking to shore the waves would lift me up and set me back down. I kept lifting my arms and pulling my waders up as high as they would go hoping I wouldn’t take on any water. This went on for about 40 ft until I finally reached the edge of the shoal. Finding a sure footing in shallow water was certainly something I won’t ever forget.

I still had to wade to the mainland but I had done that many times. As kids, my brother and I used to walk around this same stretch of beach, shotgun in hand and a sack of decoys over our shoulders. We would wade over to the island I had now currently and firmly landed upon and lay in the middle on a small pond awaiting Canada Geese or a duck desperate for a small amount of fresh water. With this experience, I knew that I could easily wade across and be safe.

Once on the mainland I began to warm up some as the wind was largely cut off of me. I couldn’t believe I had made it. Suddenly, many other things that used to be important no longer held much meaning to me. The care of how many birds were harvested on a hunt really melted away, and all I cared about was that I was alive and had a sure way out of this thing. As I got up off my knees from kissing the sandy shore and thanking God for my recent relief, it dawned on me that I had a new problem. The friends that were with me had now been out in this harsh weather for quite a long time with no shelter. I had to come up with a way to get them which I began formulating on the long walk back to my parents.

I was able to procure a boat and some gas from a friend. I called my own phone which my friends quickly picked up wondering where I was. When all of the gear was removed from the boat, so was my drybox which had my VHF and cellphone. I let them know that I had trouble with the boat but that I was going to pick them up soon in another vessel and to hang tight. This was the only plan that went right that day and I picked them up shortly after as well as towed my broken-down boat back to the harbor on the same trip. We still laugh about parts of this story every now and then, but the real meat it is not talked about much. It gets too real.

Core Sound let me go that day. She has not been so kind to others in the past. My Mother lost her first husband to the sound. Several others before and after him have been lost. She’s nothing to take lightly. The salt and the sea run heavy in my blood whether I was born with it or it was injected over the course of a coastal childhood, but I reckon my blood’s not salty enough to keep me afloat in her grip. I don’t think any of us are. She’s beautiful and always there when you need something to look at to get your mind off of the everyday stresses. But I can tell you, she’s harrrrrrrddddd to live with.

Casey Arthur

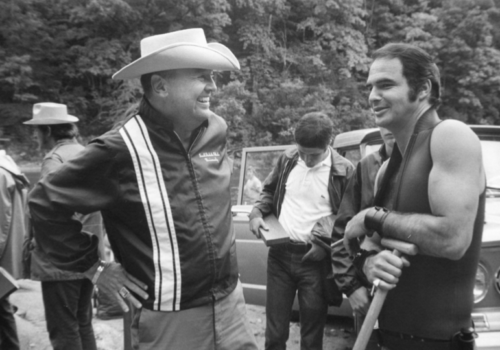

is an avid decoy maker and waterfowler from Stacy, NC, who loves to spend time on the waters of Core Sound. When not on the water, you can find him whittling and carving in his decoy shop or with his wife Julie and their two dogs, Rubie and Polly. You can follow Casey on Instagram @caseyadecoys Photo Credit: Gordon Allen Photography

You May Also Like

Gun Dogs

November 7, 2023

How I Came To Give Up On Writing- Remembering Dickey

December 16, 2022