How I Came To Give Up On Writing- Remembering Dickey

By Tim Askins

I once fashioned myself as a writer. Launched an underground newspaper. Grew my hair long in a bohemian style. Published an article or two here and there, won a poetry contest, too. I had all the bases covered. All I needed was a touch of insanity and a round of alcoholism on the side to be the next great southern voice. That previous part would come in due time.

In the spring of ’73 I participated in a creative writing workshop at USC held by the infamous, larger-than-life Writer-in-Residence James Dickey. James Dickey created his art with a passion that reflected how ferociously he lived his life. He was riding a crest of popularity with the release of the mega-hit movie ‘Deliverance’. It’s possible that everyone that attended USC from ’69-‘95 has “a Dickey Story”. Those that knew him had a “Big Jim” story. These stories had a life of their own blurring the line between fact, fiction, and myth.

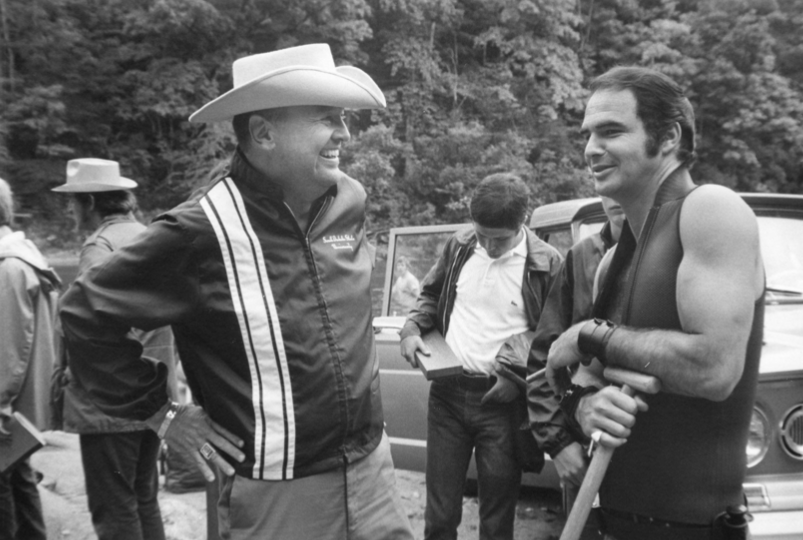

The class was held variously on the Horseshoe, in the library, in the park but never, ever in a classroom. The 6’3” broad-shouldered Dickey was an imposing figure whose presence captured center attention in any room. His athletic build was still evident even in his fiftieth year, but a bit of a paunch was belying the heavy drinking squeezing into his life. He would roll up to the gathered group five fashionable minutes late ensuring his cameo appearance would not be disrupted by some tardy, fawning undergrad. He wore a gregarious grin along with the cowboy hat and Ray-Bans made famous shooting the sheriff scene and a leather satchel full of papers and books. I had a satchel, too.

The campus was alive with the prospect of a giant walking among us that year and that giant was uniquely southern. In an interview he replied to a question,” the best thing that ever happened to me was to have been born a Southerner. First as a man then as a writer.” In an era that was ushering in a ‘New South’ Dickey’s linebacker mentality, competitiveness and military bravado exuded a masculinity at odds with the peace and love culture flourishing on campus. He was revered none-the-less.

He was big and menacing in a genteel way with perhaps an underlying, inexplicable bit of insecurity. Always careful with words, much like the sheriff when he asked the three terrified men who are trying to hide their friend’s death, ”How come you boys to have four life jackets?” The director, John Boorman, eventually banned Dickey from the set because he bothered Burt Reynolds and the other actors.

How were we, the obsequious group of undergrads, to know we were witnessing the zenith of a star? It could be said all his good words were written before 1970, with perhaps only a few exceptions. Maybe this fueled his need to become an outrageous and erratic literary showman? Maybe it was his desire to court Hollywood. In any case by 1973 he was now the show, tooling around in his Jag XKE, alcohol abuse riding shotgun. It was the same Jag he wrapped around a telephone pole in the summer of ’76.

Was he a literary genius? Many thought so. For those of us gathered in front of him, it was our first experience with genius or celebrity. I knew some smart people and had brushes with some music stars – I waited on Kenny Rogers and his wife and hung out at the pool at the Hawaiian Village with the Tams and Georgia Prophets, but how do you weigh this experience- to talk about ideas and writing and books with one of the most influential writers in American literature? To have a firsthand experience with a major southern voice?

”No true artist will tolerate for one minute the world as it is” Nietzsche remarked. James Dickey was an overman. While his entire life, by many accounts, was contrived, an elaborate bending of reality, he held the power to affect and influence the lives of others. His creativity, on the other hand, created a chimerical canvas consisting not of a single falsehood but perhaps thousands of contrivances and outright fabrications. Some were harmless, some hurtful, others deadly. In some sense, it seems James Dickey may have seldom told the truth at all. By 1973 he had perfected making himself up.

The big man on campus would occasionally read an excerpt from our work. Like eager lap dogs, we would push forward our latest creations, budding masterpieces neatly typed in double space. He would expound on finding and celebrating the uniqueness of language. He would push us to gather our creativity and the courage it takes to put it to paper. He might read an excerpt then hit you in the face with it.

“Sometimes you gotta lose yourself to find something.” If anybody said that to me today, I think I’d get out of the canoe and hike back up the mountain. But on a beautiful spring day in front of Davis College James Dickey paraphrased this famous quote in offering his advice: “You have to live a life worthy of writing about.” Dickey’s advice seemed compelling. Better advice might have been to spend more time writing and less time ‘being’ a writer.

Unfortunately, he failed to mention the necessity of intellect, vision, hard work, determination, dedication, or the time that would be spent honing the skills of a wordsmith. Those things were as normal for him as a white bread sandwich. He also failed to warn of the hell of waking up every day assaulted by the senses, the hangovers, heartaches, and dead friends that would litter the highway to losing yourself. He struggled navigating the latter, too.

Nevertheless, I stepped into those raging waters of hell with my sights on the prize on the opposite shore- finding something worthy to write. The next few years would cycle between travel and honing my creative skills – in the building trades: becoming a brick mason, cabinetmaker, and boat builder. Still, nothing noteworthy to write spilled forth on my pages.

I ate couscous with Berber tribesmen high in the Atlas Mountains, rode the Marrakesh Express, learned to do wood inlays in Casablanca. I surfed an isolated point break in Africa for two months and not another soul in sight. I learned celestial navigation and sailed a small boat across the Atlantic Ocean, I watched two dogs in the light of a new moon rising on the Bay of Campeche while shadowy men loaded the boats. Still no epiphany.

I also quit writing somewhere along the way, maybe about 1983, the same year we lost the America’s Cup for the first time in 132 years. I spent part of that summer of ’83 as captain of a fifty-foot ketch in New Port, Rhode Island amid the Kiwi invasion led by Bond and Bertrand. My friend and fellow captain Jake Farrell ran the chase boat for the New York Yacht Club syndicate. It was all fun and games until the Liberty crew failed to cover on the leeward leg of the last match race and Australia II won in the unprecedented 7th race. When I got back to Charleston that fall, I opened a cabinet shop.

Somehow through it all and by no device of my own making, I retained a tenuous grasp on the shores of reality. In 1997, after years of failing health, James Dickey was buried at All Saints Episcopal Church at Pawley’s. That same year my company was named one of the top 10 Cabinetmakers in America by ‘Cabinetmaker Magazine’. Dickey was gone and I had transmogrified into the entrepreneurial world of business.

By the time of Dickey’s passing, I had acquired a new skill set essential to entrepreneurs- the ability to forget. The failed business deals, the cacophony of NO, the accounts receivable not received, contracts breached, IRS audits: All things that could drive a normal person to the scarp of psychosis, but the true entrepreneur learns to forget the failures and thrives on it. Forgetting, I found, is a luxury the writer can ill afford. Will the New New South produce another Dickey? Unlikely.

Our current cancel culture of suburban academia is more likely to be put off by his hubris than be intrigued by the anomalous strangeness of his poetry. Given his knack for exaggerated fabrication and unreconstructed womanizing maybe that is not all bad. Then there are the diminishing interests in his topics- the machismo of the old new south. He was a Red State bubba extolling hunting and soldiering, a “Georgia Cracker Kipling” and Red it seems is not cool in the New New South.

Is there another? Someone ready to present a bold challenge to our most deeply held assumptions about the south and ourselves? A voice that disturbs our vision and challenges our assumptions about the Old South, the New South, and New New South.

Someone willing to live a life large, unafraid to “stand outside and hope to get struck by lightning”?

Someone to tell us ‘What happens when the sun goes down?’

“This is presented with the permission of the Charleston Mercury www.charlestonmercury.com, which first published this essay.”

Tim Askins

is a USCG Master Mariner and has been a licensed captain since 1980. He continues to operate his real estate development and construction business while devoting time to his farm, children, and wife, Karen. He is an advocate for wildlife habitat with Quail Forever and returning ex-convicts to the workplace with the Turning Leaf Project.

You May Also Like

Winters Hymn

December 9, 2021

My Fishing Evolution: Bigger Isn’t Always Better

October 1, 2019