Robert Ruark, “Bwana Ndege!” the Bird Master

By Edgar Castillo

Make no mistake, writer Robert Ruark was a bird hunter long before he even pulled the trigger of a rifle. The shotgun was the instrument that emotionally connected Ruark when he was a young boy hunting quail, ducks, and training dogs, with his grandfather. Though he is more well known for his wild exotic hunting exploits, much like his idol Ernest Hemingway, Ruark’s literary writings and big game accounts are also occasionally spiced with good ol’ fashion bird shooting…including, wild AFRICA.

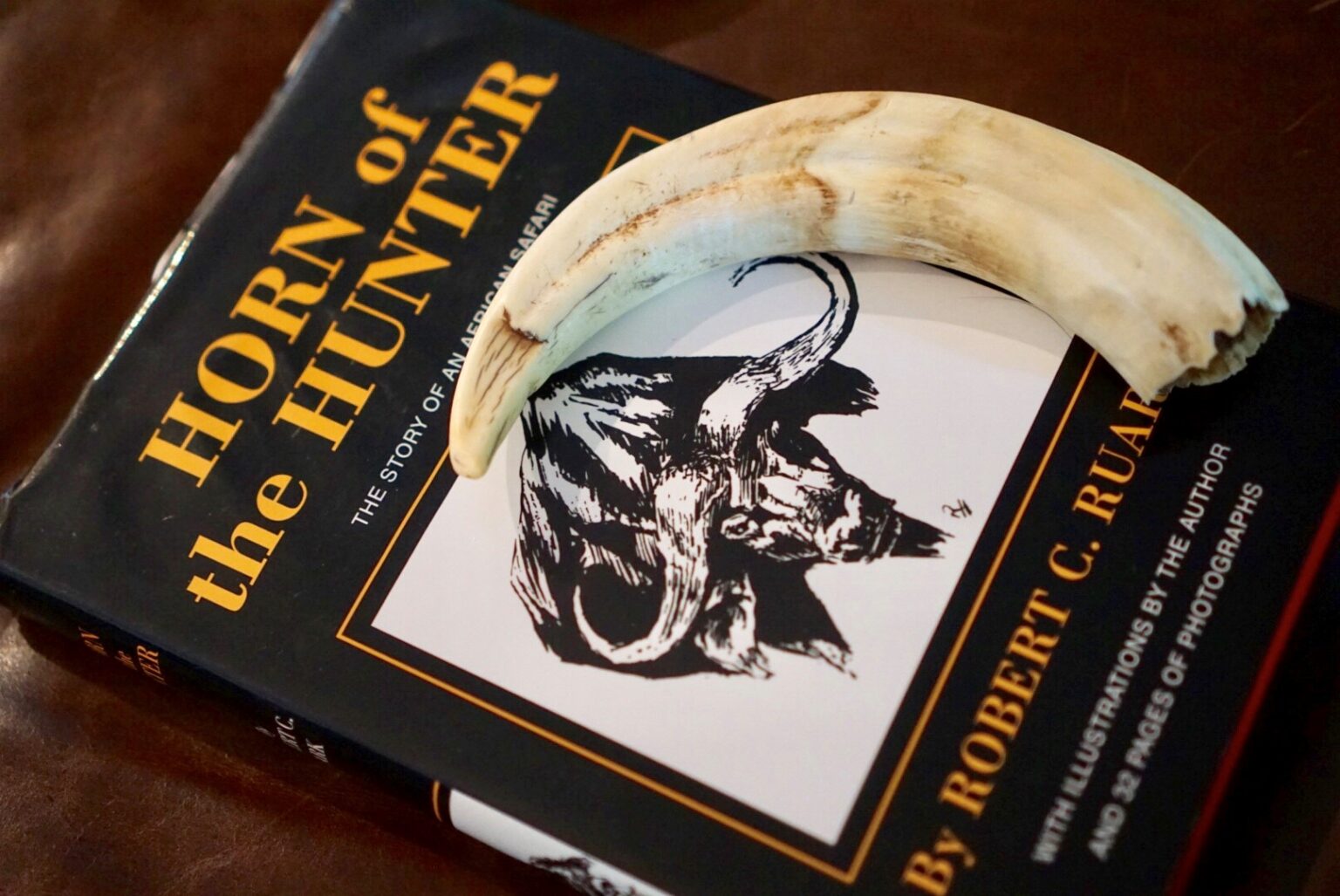

There have been many arguments about Ruark as he is regularly compared to Hemingway. He always seems to be in the shadow of his scholarly and adventurous mentor. It is well known that Ruark was greatly influenced by Hemingway. Many argue that Ruark was the better of the two when it came to writing. Some would even debate which great author was the better hunter. Ruark even followed in Hemingway’s footsteps and found himself on a three-month safari in the Dark Continent in 1951. Ruark’s experience led him to masterfully pen, “Horn of the Hunter” in 1953. Which by all accounts is probably “very arguably, the best book on African hunting ever written”, according to Field & Stream.

Ruark would go one step further and have his journey filmed. He provided the narration throughout the documentary which would later be released in the 1954 short film, “Robert Ruark’s African Adventure”. The grainy black-and-white amateur footage chronicled the entire trip, showing all elements of an African safari. However, when not capturing stalks on rhinos, lions, and leopards, Ruark shared a common enjoyment with Hemingway, and subtly showcased the spectacular wingshooting Africa had to offer.

The following is a brief overview of Ruark’s wingshooting experiences that he shares in books, film, and quotes about bird hunting in Africa.

HORN OF THE HUNTER – Book

Ruark’s epic safari for which he chronicled in the book, “Horn of the Hunter”, is riddled with exciting hunts for dangerous and elusive animals. However, Ruark takes the time to tell readers he was a “compulsive bird shooter”. Enough that starting on page 134, Ruark had to lay down the law and demand to his kind of shooting. Both his PH (professional hunter) Harry Selby, and the natives thought he was mad for “spending time and energy blasting away at birds when there are two thousand pounds of eland over every hill…”.

For over five-and-a-half pages Ruark shares in detail his need to revert to his roots with the shotgun, the noblest of weapons. With his English made Churchill 12-gauge, he was finally able put to rest his urges since stepping off the plane. Those flocks of guinea fowl, big coveys of spur fowl, and hordes of tiny quail that enticed Ruark every time they crossed the trail, were finally going to be given their own moment on the safari.

That day came when Ruark couldn’t bare it no more and shouted, “toa (to take out) the shotty-gun.”, after he spotted a duo of francolins, big-partridge like gamebirds with mouth-watering white meat. The pair fell easily to Ruark’s marksmanship, though Selby was unimpressed with the clean double on the birds. One of the natives proclaimed Ruark, “Bwana Ndege”, Bird Master.

It was at that moment Ruark decided to have a day devoted to his beloved wingshooting. Prior to leaving onto the next camp, Ruark and Selby, who would be armed with a little Sauer 16-gauge, would venture down to the watering hole, and shoot sand grouse.

Ruark knew that at precisely eight-fifteen in the morning, flights of the plump birds would arrive. Soon it became clear that Ruark and Selby had switched roles, where Ruark became the master hunter and Selby, the inexperienced aloof student.

Ruark shot twenty grouse using twenty-five cartridges, while Selby went through two boxes (50 rounds) for a grand total of eight birds. Giving up, Selby called it a day. But it didn’t end. While on their return trip back to camp, Ruark observed a flock of guinea fowl and ordered Selby to stop the jeep. Ruark rushed the group of birds causing them to flush. He emptied both barrels, procuring two guineas. Ruark’s prowess with the shotgun was enough that Selby had no words to say. Ruark had proved his point that wingshooting was indeed sporting.

The book continues focusing on a variety of hunts for big game animals and in Chapter 9, Selby finally acknowledges Ruark’s affair with wingshooting and tells him that he will be able to “shoot your bloody birds to your heart’s delight…” while in N.F.D (formerly known as the Northern Frontier District, now referred to as Kenya). Snippets abound with Ruark making comments throughout the remainder of the book on how much he just wants to go bird hunting across the savannah and bush…“My mouth was watering at the wildfowl.”

It’s also apparent that Ruark’s wife, Virginia, also partook in wingshooting in and around camp. Two black-and-white photos depict evidence of her ability with a shotgun. Handfuls of sand grouse, guinea and spur fowl met their demise at the hands of “Mama”.

There’s no doubt the book is about big game hunting, but Ruark does a wonderful job singling out here and there the importance for his first love of wingshooting and incorporating it into the safari.

ROBERT RUARK’S AFRICAN ADVENTURE – Film

Upon landing in British East Africa (BEA), Ruark and his wife, Virginia, meet up with Harry Selby, a professional hunter. After all the gear and provisions needed to live and survive the long trek are procured, including an armament of firearms, the convoy of vehicles set off.

The heat and environment cause the band of cars to stop briefly to cool off the engines and fix a tire. Ruark takes the opportunity to climb an anthill to get a better view of the landscape. Using binoculars, he observes a variety of animals, including a flock of Guinea fowl. The plump, cartoonish-looking birds are scratching their way up and down a donga, a dry riverbed.

Ruark relays to the viewers,

“They form a staple in our diet…” and “…cold, boiled with mustard, they taste mighty good.”

Soon they are back on track and the caravan finds itself stopping in Masailand. There they set up their first temporary encampment, and Ruark provides a glimpse into camp life. He narrates the variety of chores performed by the hired native help. One of the most important jobs is preparing and procuring food. Ruark’s wife, Virginia, and Harry see an opportunity and go to a nearby watering hole for some pass shooting.

Ruark says…

“This day we intend to dine on grouse. Sandgrouse. A wonderful desert bird about the size of a partridge. He comes to drink at the waterhole, and he swoops and darts like teal in a hurry. You’ll miss more of these than hit. But they make wonderful eating.”

The scene is beautifully captured, showing Virginia and Harry toting side-by-side shotguns, probably 12-gauges, as sandgrouse flutter about. Crouching behind what appears to be a scraggly bush, the two shoot at small groups of grouse that come in for a drink. Larger flocks descend in and out rapidly. Shots ring out and birds are seen falling from the sky.

Ruark narrates…

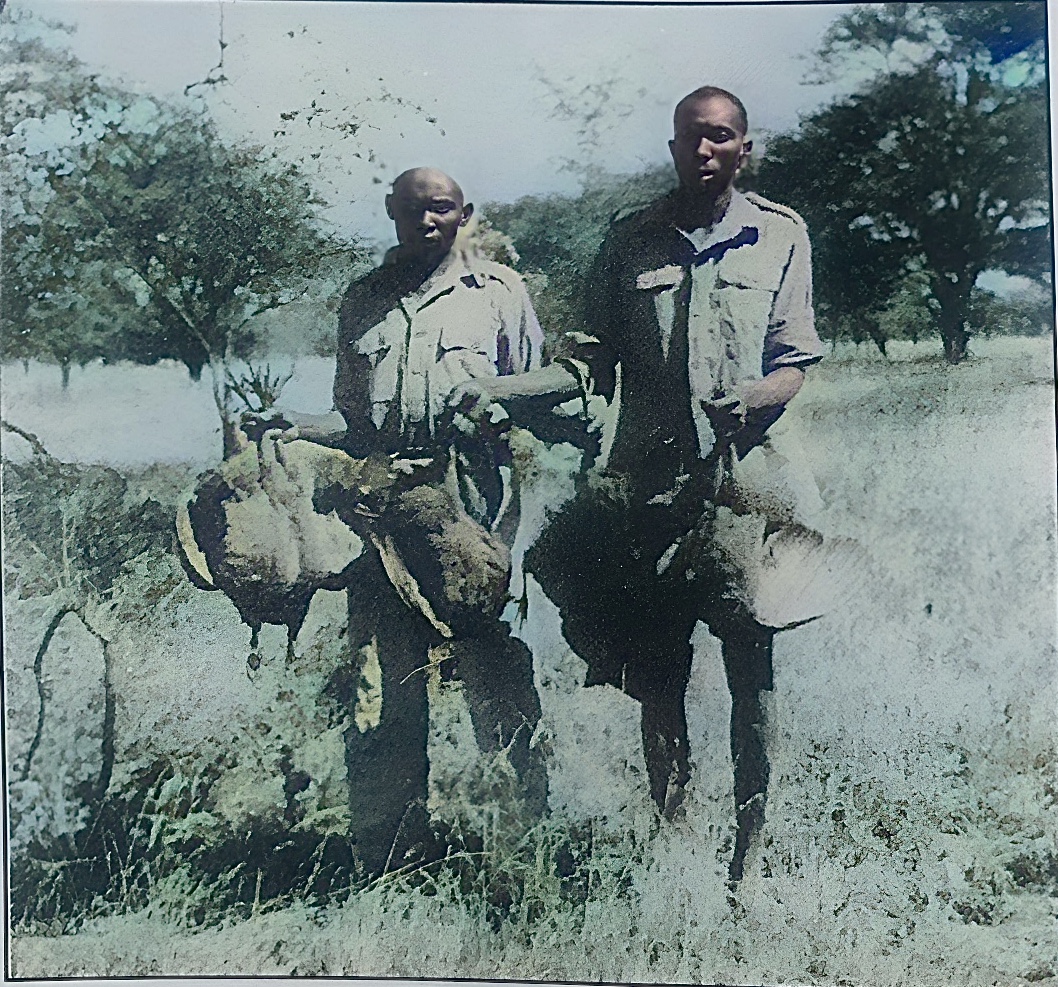

“The human bird dogs, Natheka and Chalo, go to search for the ingredients of dinner, and come back laden.”

They two African natives are seen carrying at least seven sandgrouse in each hand. Virginia is seen holding and admiring the birds, but Ruark declares he would much rather have them popped into a skillet.

The recorded scene thus ends what we know briefly of Ruark’s African wingshooting encounters in the film.

ROBERT RUARK – Quote

On Safari:

“… big coveys of ostriches and armies of guinea fowl. The big, fat, yellow-necked francolin flapped and squawked and scratched in the track, sand grouse carved their jet trails in the skies, and the tall thorn trees erupted big blue pigeons…” – The Lost Classics of Robert Ruark

On Sandgrouse:

“The sand grouse is closer to the pigeon family than he is to a grouse, but he is stripped for speed and beautiful to watch when he flies and he is also beautiful to eat. He is a plump little fellow speckled in brown, buff and black, and while his meat is dark I never saw anybody curse him when he turned up in a pot roast. … . A pintail sand grouse coming in with his eye fixed on a waterhole is logging fifty knots or better, and when he swoops he makes a Mexican white-wing dove look clumsy and slow. He comes just once a day to dip his sharp little bill in the water.” – Horn of the Hunter

Ruark didn’t know it, but at the time he was giving readers of his book and viewers of the film very small doses, yet important glimpses into his love for bird shooting. Because when it came to hunting, Ruark was plain and simple a wingshooter first.

Wingshooting was Ruark’s way to return to that time of innocence where the whir of wings catapulted his heart. It had been ingrained into him as a young boy, for which it laid the groundwork for Ruark expanding his adventures afield.

Ruark’s brief passages on bird shooting were just enough to whet his own appetite, for it had been growing since beginning the safari. The shooting of birds not only supplied camp food for the pot but provided a sense of elegance and refinement surrounded by death, decay, and maneaters while carefully walking the tall grass. The wild country offered so much more in the way of wingshooting…doves, sand grouse (double-banded, Burchell’s, and Namaqua), and the partridge-like francolin, or pheasant-size guinea fowl, both occurring in multiple species, as well a smorgusborg of waterfowl.

Ruark saw the rich shotgunning opportunities the land had to offer, and wanted to make sure it didn’t go unnoticed. Words and images were what he used to share the new love he encountered, wingshooting Africa.

Edgar Castillo

Edgar Castillo is a recently retired law enforcement officer for a large Kansas City metropolitan agency. He also served in the United States Marine Corps for twelve years. Edgar’s passion lies in the uplands as he self-documents his travels across public lands throughout Kansas hunting open fields, walking treelines, & bustin’ through plum thickets in search of wild birds. He’s a contributing writer for several publications and e-magazines/websites. Follow the author’s adventures on Instagram @hunt_birdz

You May Also Like

Ruby & Woodcocks

December 20, 2019

Cast Horn Designs

March 14, 2022