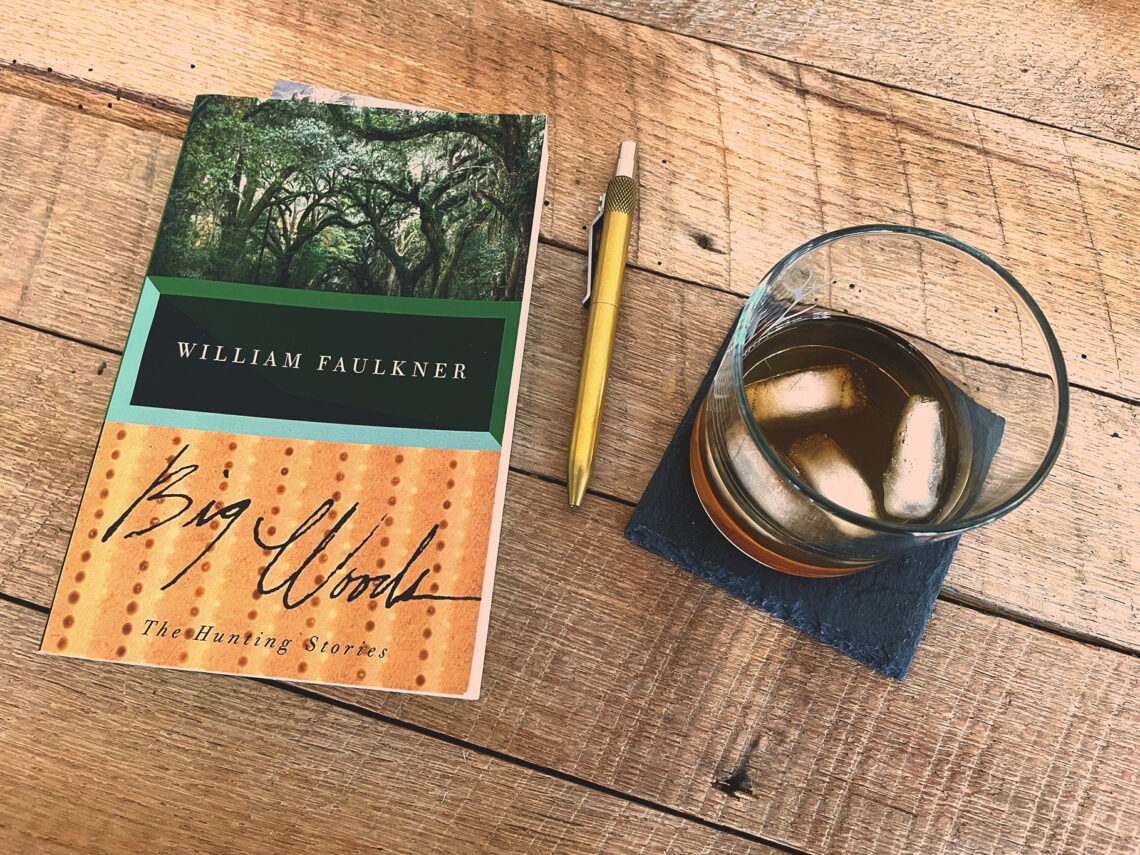

Big Woods :Review

By Matt Ludwig

If you’re like me, the name William Faulkner does not evoke the image of a rugged outdoorsman. Instead, it conjures a little white-haired man in a suit, dark-eyed and mustachioed, always posing with a pipe. Such is not the case with his contemporary, Ernest Hemingway, whose safari “grip & grins” depict a sporting life inseparable from his literary legacy. But Faulkner hunted too. From his teens until his fifties, he spent half of November in deer camp, chasing buck and bruin through the wild Mississippi Delta. This region’s canebrakes, ancient timber, and bayous inspired the northwest corner of his fictional Yoknapatawpha County, where the hunting stories collected in Big Woods take place.

Faulkner published Big Woods in 1955 after revising four previous pieces: “The Bear,” “The Old People,” “A Bear Hunt,” and “Race at Morning.” He placed an epilogue between each, adding history and perspective to the preceding action. In “The Bear,” a yellow-eyed hellhound finally defeats the legendary bear, Old Ben, who has raided the Delta’s homesteads for years. Great stags elude hunters in both “The Old People” and “Race at Morning,” but their cunning teaches the stories’ young protagonists that there is more to hunting than the kill. And in “A Bear Hunt,” an African American servant settles an old grudge with a white hunter using the help of his Chickasaw friends.

The character Ike McCaslin appears in all the stories and is the link through which Faulkner tracks time and change. He’s the protagonist in “The Bear” and “The Old People,” growing from a boy to a young man and learning woodsmanship from his Choctaw mentor, Sam Fathers. In “A Bear Hunt” and “Race at Morning,” he appears only briefly as the old man and hunt-master now known as “Uncle Ike.” The epilogues of these last two stories capture his reflections on a lifetime of hunting in the Delta. Just as in the real Delta during the early Twentieth Century, roads and railways moved in to ship the timber out, clearing the land for cotton fields and the dams to protect them. The wilderness shrank and retreated further and further south every year, and Ike followed season after season. In the book’s last scene, he lies awake in camp and says to himself, “No wonder the ruined woods I used to know don’t cry for retribution. The very people who destroyed them will accomplish their revenge.”

Because Faulkner chose these stories from across his career, the book offers a representative sample of his art and an easy entry for those unfamiliar with his singular style. A common, lazy comparison between Faulkner and Hemingway is that the former wrote long sentences while the latter wrote short ones. This does nothing but dishonor both. The important difference is not in the length; it’s in the effect. Hemingway’s sentences move straight and measured like jabs, sweeping you across the romantic landscapes of Spain, the Alps, and Africa. Faulkner’s sentences branch and twist like bayous.

They don’t sweep; they meander, immersing you so deeply in the setting and characters’ minds that you might feel lost. And then the course veers back into the main channel just upstream from camp, where you arrive wet, dirty, and covered with briar scratches. But like any hunt worth a damn, you’ll feel the satisfaction of having endured. It’s a hunt you can enjoy with your feet up, so put a log on the fire and some bourbon on the rocks and follow the baying hounds into Faulkner’s Big Woods.

Matt Ludwig

Although he’s a Yank born and raised, Matt holds a deep appreciation for Southern sporting culture, derived during his Army years at Forts Bragg and Benning. He splits time between Cincinnati and his childhood home in the Appalachian foothills of Ohio.

You May Also Like

My Fishing Evolution: Bigger Isn’t Always Better

October 1, 2019

Six Miles to Charleston

February 18, 2021

8 Comments

Adam

Well written.

Matt D

Heck yeah man! Well done! Proud of you!!

Stephen Buck

Amazing article. Makes you want to do exactly what Matthew suggested, log on the fire, and bourbon in hand. Nicely done.

Lis

Very descriptive and painted a perfect picture in my mind. So happy to see this!

Maggie Boineau

This review stirred up lots of interest to read this book! I am certainly looking forward to it! Thanks so much!

Gary

Nicely done. We need more “what it is like” stories and fewer “how to” or ” what I did” articles. That’s why writes like Faulkner still resonate and transcend the recycle bin.

Brian

Matt’s feathery descriptions drove me on a pink, velvetry drive, dreaming of Quarter Pounders, Pretzel Heads & Mega-Toads. If only I were allowed to own a rifle in the great state of Michigan. If only I could get back to the bayou. Matt, can you imagine what it would be like in Faulkner’s deer camp? A breakfast of grouse hash, runny eggs & a little coffee in tin cup full of Old Crow. Excellent prose, sir.

Edgar Castillo

Very well done Matt! You’ve inspired me to checkout this book and see what I’m missing out on. Looking forward to seeing more from you here at F&W