South Africa Warthog Adventure

By Stephen Thomas

It was day four of my African safari and I had already taken three of the animals on my Most Wanted List. The only thing standing between me and hunting a bushbuck was a boar warthog.

I bang-flopped my blue wildebeest on Day 1 but Nic, my Professional Hunter, had me put an insurance shot in him. I found out with an email from my taxidermist in South Africa after I got home that the wildebeest qualified for the record books. Being an official Rowland Ward measurer( Rowland Ward is a record keeping organization of game taken around the world) , they filled in the measurements then emailed me the form. I signed and sent off the paperwork. I got a cheerful phone call from Rowland Ward a week or so later telling me that it would be published in their next edition. Africa is like a real-life Disney World: it seems to always find a way to exceed already high expectations.

The second and third animals, a zebra stallion and impala ram, were one-shot kills that never got out of our sight. Early on, I had tried to warn Nic that I am not always a good shot but he and the tracker, Big John, were starting to think I was sandbagging. I wasn’t.

Up until today, we had been spot-and-stalk hunting but, for some reason, even before coming to Africa, I had been fixated on the idea of killing my warthog over a waterhole. Good PHs are nothing if not good listeners. We did try a few blind stalks early and spent the better part of the morning photographing birds. I’m a very serious birder so getting new species on my life list was a close second to the big game hunting I had planned. The 27-year-old Nic, started his professional life as a photographic safari guide and was a genuinely good birder himself but as the day heated up he suggested it was time to get the waterhole.

I carried my gun and camera into the blind. Nic took his .375 H&H and radioed for lunch to be brought to us. He left me in the blind, alone, with instructions to shoot a big pig if I had the chance. He slipped out and walked to the road to get our lunch. If anyone wants to see the birds and other animals of Africa, there’s no easier way than sitting over a waterhole. I photographed probably a dozen different bird species including blacksmith plovers, arrow-marked babblers, and a tiny raptor called a shikra. Big animals started showing up around noon. A really big sable bull with an oxpecker jockey let me get a couple of photos but he knew something wasn’t right and didn’t stay long. A timid bushbuck ewe came in and got a few nervous drinks then bolted back to cover. By the time Nic got back to the blind, the warthog show started.

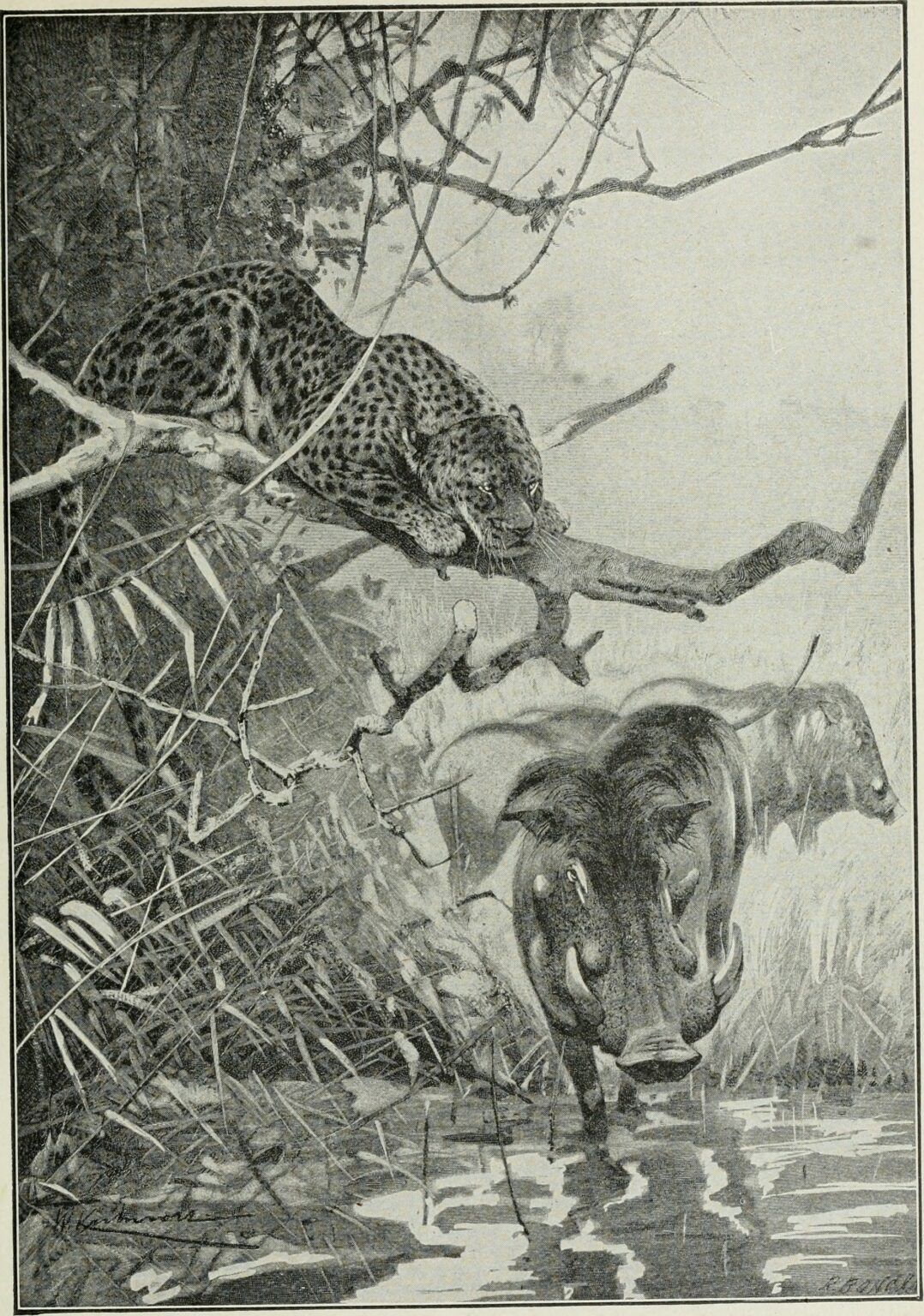

They came from just about every direction – At first, the groups were sows with young of various ages. Nic quizzed me on each little pig – whether it was a male or female. Females only have two facial warts and males have four but they’re small when the pigs are small. Something I never knew was that young warthogs have a line of white whiskers that, at a distance, look like tusks. It is nature’s way of making them look more capable of defending themselves than they really are. With the distraction of birds and baby warthogs, I forgot that I was hunting…until Nic said, “big pig…get your gun.”

I was caught totally flat footed. I felt like an offensive tackle getting hit in the back of the helmet by a pass when I was blocking for a run play. I really can’t remember what I did with the camera or how I got to the gun. The pig was coming from a thick patch almost directly across the waterhole. He walked around the rim of the waterhole to my right giving me a broadside shot. He’d stop every few steps and look around. “That’s a shooter if you want to take him,” Nic coached.

My conscious mind knew there are certainly better pigs around but I wasn’t unhappy with this one. Besides, I was ready to move my focus to the next animal on the list. I lined up and shot.

The pig wheeled around and took off in the direction he had come at a full warthog sprint, which isn’t slow, but didn’t act hit. He covered the 40 or so yards of open, red dirt before he reached the thicket and if he did I’d lose him.

I don’t know if he paused at the edge of the brush or if it was one of those human things where time just seems to stop, but with him facing almost directly away from me, I put the second shot from my break-action .30-06 into his left ham aiming across his body to the opposite front shoulder. There wasn’t any real conscious thought other than to slow him down and hope the first shot was lethal. I saw a reaction to the second shot in the instant before he disappeared in the thicket.

Nic’s face told a story that I didn’t want to hear. “Why’d you rush that shot? You didn’t need to rush your shot…”

Struggling to answer his question, “I don’t know,” was all I could get out. “Did I hit him with the first shot?”

“You pulled your shot. You hit him back.”

Nic’s words made it sound like he suspected a gut shot but I just didn’t believe that. I had a clear mental picture of where the crosshairs were when the gun went off. I don’t know why but I had actually aimed my shot in the ribs rather than straight up the center of the front leg like my previous shots on this safari. I know I didn’t jerk the shot but I clearly remembered picking a spot on his ribs…why did I do that? Maybe my shooting problem has been mental rather than mechanical all along. The more immediate problem, though, was a wounded warthog.

I saw 10 different emotions run through Nic’s face over about 2 seconds before he leaned back in the flimsy chair saying that we needed to wait for a while. Almost instantly, he fidgeted himself back to vertical and said, “nope, we’ve got to go now.”

It was clear that the mess I just created didn’t lend itself to an obvious next step. I put two fresh shells in my gun but left it broke open. Nic grabbed his .375 H&H. My instinct was to head straight to where we saw the hog go into the brush. Nic said, “Nope. We start back here”, as he headed to where the pig was when I first shot. There was some dark red blood. I hadn’t missed but it didn’t look like lung blood either. Nic smelled it saying something to the effect that it didn’t smell like a gut shot. Nic followed each hoof print leaving a scrape with the toe of his boot each time he found blood. The scrapes were getting further and further apart then we reached the wall of brush. Once again, he drug his finger through the blood in the dirt and checked it. This time he said, “stomach contents, probably from the second shot”.

It was my turn to run through a full set of emotions. The only thing for me to do was to turn the entire situation over to this kid who is younger than my own son. He was the PH. Regardless of age or any other factors. He was in charge. “Okay, what do we do?” I asked.

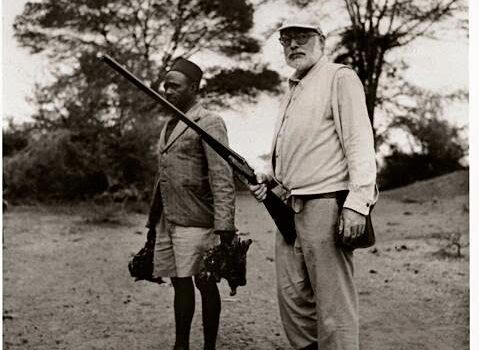

Nic’s entire demeanor changed. He turned his pack around, dug out papers and tobacco, rolled and lit a cigarette. He bumped the rim of his hat with the back of his hand. I was beginning to think of him as a young Mick Dundee but now he looked more like the middle aged Robert Ruark. I don’t know if his transformation was a premeditated act or a legitimate result of the seriousness of the situation. He cycled the bolt on his .375 showing me he had a bullet going in the chamber then pushed the bolt closed. The sun was blistering hot. “Stick close. If we see this pig, I’m shooting it,” he said. I closed my gun too. He smoked about half of the cigarette then put it out in the red dirt and stepped into the brush. I stayed right behind him.

Somehow, he and I had become characters right out of a dozen safari stories I have read. Worse, I was playing the role of the schmuck client who had wounded an animal, and he was the PH charged with sorting things out. It was so surreal that I had to coach myself into taking it as both very real and very serious. I needed to stay alert and aware.

Nic’s tracking job through the waist-high brush looking for Schrödinger’s warthog was painfully slow. He followed every quarter-step of the pig without taking his eyes off the brush directly ahead of us. I expected the bush on either side of us to erupt with an angry warthog at any moment. It was hot. I wanted to wipe the sweat from my eyes with my sleeve but was afraid to. I almost knew that that would be the moment when the razor-tusked pig would charge. I let the sweat stream across my face. I regretted not guzzling that bottle of water I left in the blind. One slow step after another.

It was less than 5 minutes and it wasn’t far, maybe 30 yards, before Nic straightened up. He notched his chin up in the air and stepped around behind me. I was confused. “There’s your pig.” It was only about 10 feet in front of us lying on his right side but it still took a moment to make out his left tusk sticking up in the brush. It reminded me of a kid’s bike thrown in the long grass at a fishing hole with only a handlebar sticking up out of the grass.

He wasn’t struggling but was still breathing with shallow, labored breaths. I stopped that with one more shot. Nic was a morbid ballistician so couldn’t wait to drag him out into the open and examine his wounds.

The first shot was a pass-through but, as we both suspected, pretty far back. It either got the back of his lungs or his liver, maybe it split his diaphragm. The second shot broke his femur and tore through his stomach then, if it made it that far, into his chest cavity. It wasn’t pretty. It took two shots plus a finishing shot but I had my warthog. The only consolation was that I didn’t lose him and that the PH didn’t need to finish the job for me. These are very real risks to anyone who plops down his money and jumps on a plane to Africa. I knew the risks and for me, these risks almost became a reality. It’s these risks, though, that bring us to Africa in the first place and bring us back again and again after that.

Stephen Thomas

Stephen Thomas’s fascination for birds, backpacking, and native plants is driven by a lifelong obsession with duck and whitetail hunting. His Dad introduced him to duck, dove, quail, and deer hunting when he was 12-years-old and that’s all it took. Steve is married to his high school sweetheart, has two self-sustaining adult children, and still gets to hunt deer with his now 83-year-old Dad.

You May Also Like

Whiteville, NC : Burgertown,USA

February 27, 2023

Five Quotes About Whiskey

January 17, 2020