If They Could Talk

Text By Jamie Cameron. Photos by Jennifer Rodriguez

I’m not much for collections, though that hasn’t always been

that way. As a kid, I collected comic books and baseball cards, but for all the

wrong reasons. I read the comics and I looked at the cards. I liked organizing

them and archiving them, but I didn’t love them. The cards and comics

represented my first financial investments – stuff I hoped one day would make

me rich. That never happened of course. My entrepreneurial instinct has never

been very keen. They sit in boxes and 3-ring binders in the closet waiting until

the time is right to be handed over to my nephews. Maybe they will be able to

find honest joy in them that I never did.

If ever there was a pastime that produces artifacts begging to be collected, it

is that of the sportsman. Antique fishing lures, ancient duck decoys, bamboo

fly rods, old guns – it’s all there. I know a few passionate people who collect

such things and I am always grateful for their zeal. It gives them a connection

to the generations of hunters and fishermen who shared our affliction. I

understand the magnetic pull they exert, but I have little desire to acquire

such things and decorate my house with them.

In spite of this, I do own a few relics of days afield and they are among my

most cherished possessions – perhaps not for their historical importance, but

for the stories behind them.

The Block from the Desert

When I was in middle school, we took a family vacation to Arizona one winter. Mom had a childhood friend who lived in Phoenix, who we stayed with a few days before hitting the road in a rental car and heading north toward the Grand Canyon. Like most of our outings, we didn’t really have an itinerary to stick to – just follow the road and see where it went.

Somewhere along the line, we stopped at a motel off the highway. I can’t remember where it was, but if you can picture a long, isolated stretch of asphalt cutting through the darkness of the desert at night and a glowing neon “vacancy” sign, you’ll know the place. The man in the lobby who checked us in was an elderly fellow with a sparse gray beard and kind eyes behind wire-rimmed glasses. He was strong and leathery. I thought he looked like a cowboy. Curiously, the front counter he stood behind was a glass display case filled with duck decoys and they were for sale. If you can imagine a stranger place to find and buy an antique duck block than that rundown

I’ve had her going on 25 years now and that hen scaup still holds a place of

honor in our house. I once took the duck to a renowned decoy carver on the

Carolina coast to see if he could tell me anything about its history. Without

any identifying stamps or signatures, all he could venture was that it is a

factory-made block of relatively little value. Since then, I’ve been told it’s

a 1950s era product of one of the Pascagoula, Mississippi decoy factories. To

me, her monetary value is inconsequential to the tale of how she came to be in

my living room.

The Streamer Wallet

My grandfather on my father’s side was a fisherman. Though I cannot recall any time he and I went, my father says Grandpa dabbled in all variety of angling pursuits. One year it would be surf casting, the next it would be jigging for mackerel. His constant favorite, however, was bass and he liked nothing better than to troll balsa wood plugs from a 2-man canoe around the edges of a lake. Long before he died, more than 20 years ago, Grandpa started handing down his fishing equipment to me. I have old Shakespeare bait-casting reels and an ancient tacklebox filled with giant spinners that must have been meant to catch muskies or pike. Most of the stuff is up in the attic, but I do keep a checkbook-sized streamer case from Grandpa’s days chasing salmon in northern Maine.

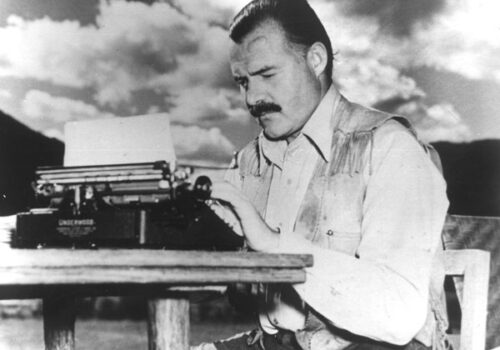

The flies are bedraggled at best, but as of 35 years ago, they still caught fish. I remember using the impossibly long bamboo fly rod Grandpa gave me (its location now a mystery to me) and teaching myself how to cast on an open stretch of the Charles River, just south of Boston. With his instruction echoing in my head, I cobbled together a serviceable blend of rotted fly line, sun-brittle monofilament leader and one of those threadbare salmon streamers. I rode my bike down to the river nearly every day after school and flogged the water with sledgehammer presentations. I will never forget the day I felt a strike as I stripped the great streamer across the current. The fish was strong and I had visions of a giant brown trout coming to the net. After what seemed like an “Old Man and the Sea”-like campaign I managed to beach the 14-inch sucker, which I’d foul-hooked just above the tail.

Shortly after that great struggle, I reasoned the flies and tackle should probably be packed away for safe-keeping and posterity. The L.L. Bean leatherbound book of streamers, however,

The “Sweet” 16

I own few guns; a deer rifle and a 20-gauge slug gun, a cheap .22 and a 12-gauge shotgun for everything else. They are utilitarian – tools for the job, nothing more. Given half the chance to trade any of them for something more effective, I would do so without remorse. When my wife’s father, Hank, decided to give me his old shotgun 12 Christmases ago, I was happy to have it for the simple fact of adding another tool to my arsenal. And then I took it out of the cloth sock it was wrapped in.

The gun is a double-barrel L.C. Smith Field Grade in 16-gauge. It is light, it swings beautifully and it flies to my shoulder when I mount it. I am in love.

I have found the model was produced by L.C. Smith between 1945 and 1950. There were more than 53,000 made during that period and they are considered to be fine guns of considerable value. When I took the shotgun to a local gunsmith to have the rust and pitting rubbed out and the barrels re-blued, he acted like one of the celebrity appraisers on “Antiques Roadshow” when they are presented with something special. “This gun has value,” he emphasized as he handed it back to me. “Thank you for bringing it in and letting me work on it.”

In it’s current, restored condition, the gun must be as beautiful as the day it was when my father-in-law received it as a teenager. The only thing about it that isn’t “factory” is the finish on the receiver, which Hank apparently took a blow-torch to make it look cool (or whatever the 1940s equivalent to cool was). I have no intention of packing the gun in oil and sticking it in the closet for safe-keeping like a pack of baseball cards or a stack of comic books. Fine old shotguns are not meant to be retired, they are meant to be shot and I’ve used it to take a wild turkey in North Carolina and upland birds in Kansas. This particular piece of history is going to keep on living for as long as I am its caretaker.

Jamie Cameron is a Yankee transplant to the mountains of western North Carolina, where he lives with his wife Sue, two rescue dogs