Thoughts of Hunting at the Temple Site

By William Hess-Martin

It is midday, and the heat is sweltering, yet there is a certain comfort in meeting it. I am the sole visitor here today, the only person, save for the security guard posted at the front gates, to experience this ancient place in the stillness of the hour. The marshlands of south-eastern Attica stretch around the site, the green expanse offering a serene backdrop for the temple ruins, while yellow hills rest sunburnt in the distance. The landscape around Brauron, both wild and calm, is a fitting tribute to Artemis, whose domain spans both the untamed forests and the waters’ edge. As I walk the path leading to the ruins of the Temple of Artemis, I cannot help but think of the rites once enacted here—rituals entwined with the sacrifice of a sacred bear, an act both revered and shrouded in mystery.

In ancient times, girls devoted to Artemis were called arktoi, or “bears.” These young virgins underwent initiation rites at the temple, a portion of which included the killing of a bear—considered sacred and embodying the wild strength, maternal care, and primal femininity of Artemis. The sacrifice was not mere violence; it was an offering to the goddess, reaffirming her role as protector and provider of life. Through the bear’s death, the community acknowledged the cycles of life, death, and rebirth that Artemis governed. The ritual symbolized balance—nurturing and destruction—and reinforced Artemis’s role in ensuring harmony with the natural world.

Seated in the shade of a broad-leafed fig tree on an age-worn slab of stone, I listen to the calling cicadas. My eyes wander over the ancient columns and walkways of the temple site, stopping on the small Orthodox chapel built upon the rock beside it. Plucking a late-season fig from the bent bow overhead, I peel back the skin to reveal its interior. The fig, with its rich, rounded shape and delicate chambers that cradle seeds within lissome folds, holds an undeniable feminine symbolism. Yet, it is not the eroticism of Aphrodite that fills this space. Instead, it is the more procreative aspects of femininity that resonate. Though Artemis is primarily known for her hunting prowess, she was equally a guardian of women, ensuring their safety during childbirth. The temple, dedicated to this dual role, was a sanctuary for women seeking Artemis’s favor during their most perilous moments. I take a bite, and the taste of the sweet and earthy fig delivers a sudden reminder of the resinous scent of the pine forests of our family property. Transported in thought, I sit on a mossy heap of fieldstones, watching the forest around me. The stones I am perched upon had been placed by people nowhere near as ancient as those that set the ones that make up the temple, yet the allusion to the great past of humanity resonates within both.

Now, reclined against a tree in the heat of the Mediterranean summer’s day, I think about the coming harvest season—rabbit, grouse, deer—and wonder if my pilgrimage to this place will somehow set me within the favor of those forces that decide the cull and set the quarry before the seeking eyes of the hunter. Perhaps, at most, the memory of having walked in these distant lands, as I step so carefully on my still hunt through the shadowed, North American woods, will fan the flames of desire and keep my focus true on the ritual ahead.

William Hess-Martin

is a hunter, writer, and artist from southern Quebec. His work delves deeply into mythological and psychological themes, particularly the complex relationship between humanity and the natural world. Drawing inspiration from his experiences in the wild, he explores how ancient myths and modern sensibilities intersect in the human experience of nature. Social Media: Instagram – @venatic_opus

You May Also Like

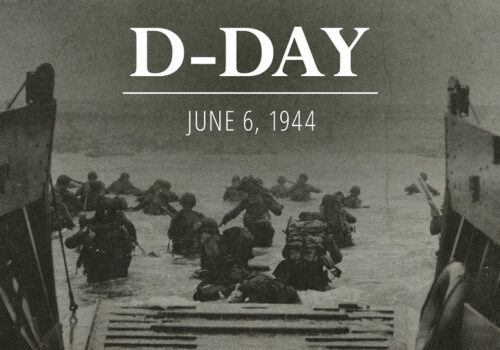

D-Day’s Unlikely Witness: Martha Gellhorn, the Woman Who Stormed Normandy

June 6, 2025

She’s Hard to Live With

February 2, 2022