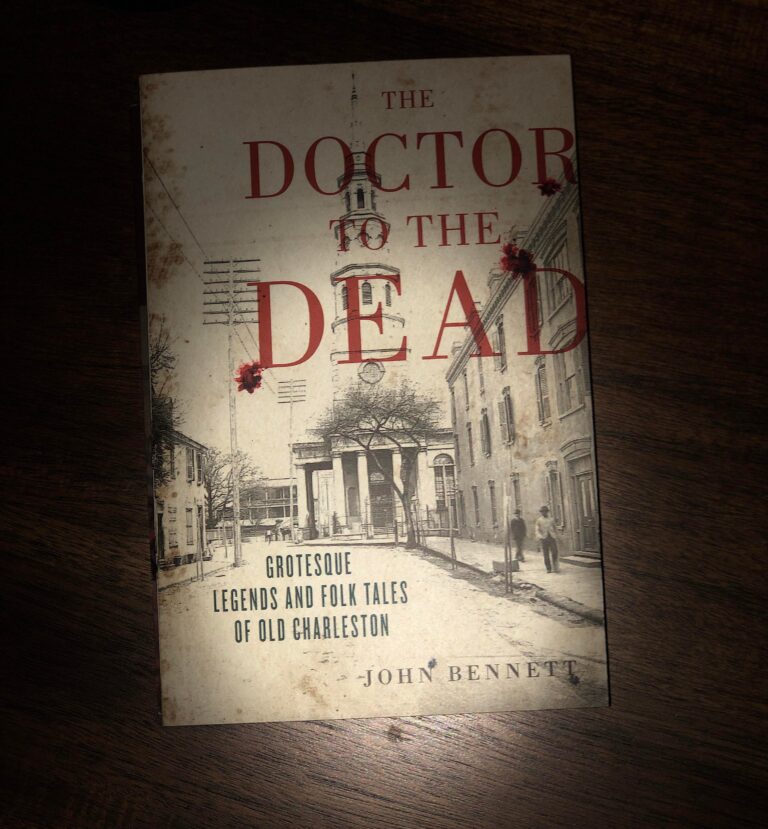

The Doctor to the Dead

By Michael Maynor

Confederate dead rising from their graves to help General Lee, a captive mermaid that must be returned to the sea to keep the city from flooding, a man that refuses to accept the fact that he is no longer among the living, and a medical doctor that turns his back on the living to be a physician for the dead. These are just a few of the stories found within the pages of The Doctor to the Dead: Grotesque Legends and Folk Tales of Old Charleston

There are many things to love about Charleston, from the food, the history, the shopping, and the nightlife: the city has a heartbeat unlike anywhere I have ever been. But one of my favorite things about the city is her ghosts. You can’t have a city as old as the Holy City, nicknamed because of all the Churches, and not have your share of ghost stories, but in South Carolina’s most haunted city, it seems there is a ghost or ghost story around every corner. I mean, the town is responsible for influencing The Raven himself, Edgar Allan Poe–– in more ways than one, but that is an article for another time!

John Bennett, a native of Ohio, came to Charleston in 1898 and married a woman well connected to Chalreston’s high society. Bennett became fascinated with the Gullah language spoken by most blacks in nineteenth-century Charleston. Gullah is one of the last remaining forms of the pidgin-dialect in the United States but at the time was spoken primarily by blacks living in the coastal regions of South Carolina and Georgia.

Gullah is a mixture of English and central and west African languages. When Bennett was doing his research and documentation, he did not have the luxury of being able to record actual audio of his subjects as he collected their ghostly tales. Hence, the book contains the author retelling and reworking the stories told him.

In Bennett’s own introduction to his book, he states that he needed to translate “the well-nigh incomprehensible dialect spoken by the primitive black folk of the South Carolina coast” lest the tales “highly dramatic quality” be “lost of obscured in the grotesquery of the original dialect.” Bennett wanted to secure these stories, and he made a decision to put them into plain English so the message would not be lost. Bennett wanted to be the authority on the African Americans of the Lowcountry. While there is debate on whether Bennett’s reworkings of the stories make them inauthentic, that much is up to the reader to decide. I am just thankful they were not lost. The last three stories within The Doctor to the Dead are written in Bennett’s “modified Gullah.”

The Lowcountry is a magical place filled with legends and folktales, and many have been lost to time. Thankfully, there are still books like this that exist to preserve these ghostly tales of the region. While they might not be written perfectly, they are there as a record for those in generations fascinated by the ghosts of the Holy City.

Michael Maynor

I am a proud native of North Carolina with a deep love for the sporting lifestyle and everything Southern. My book collection seems to grow endlessly, and I have a particular fondness for collecting vintage duck decoys. Despite appearing content, my heart longs to return to Africa for another safari adventure. John 3:16

You May Also Like

Baobab Lounge: Savannah, Georgia

July 29, 2022

“I’ll Have A Double!”: Holiday Party

November 21, 2022