Danger!: Hippo Hunting in Zambia!

By Michael Maynor

It was our first morning in the Luangwa Valley of Zambia, and hippo was on the morning’s agenda! My hunting companion, Charles, had wanted a hippo for some time, and after an unsuccessful hunt in Zimbabwe the year before, he opted to try his luck in the hippo-rich waters of the Luangwa. The Luangwa River is one of the four major tributaries of the mighty Zambezi River. We were hunting in July during the dry season which runs from April through December when the river has fallen considerably. The Luangwa has the highest number of hippos in Africa with an estimated population of 25,000 animals, so the odds were in Charles’ favor as we set out on the morning’s hunt. Though before we hunted, we had to locate our Zambian game ranger

A good portion of the morning was spent looking for our Zambian parks/wildlife ranger. Zambian law requires that a ranger accompany hunters in the field. It took awhile to locate the ranger, but it gave us a chance to see sections of the local villages. Ultimately the ranger was located, and we could now get to the business at hand of hunting a hippo.

We drove to a section of the river where the hippo were congregated. There were three different pods totaling at least 50-60 hippos and one further down the river from us with about 25 more. We parked a good distance from the river and started glassing the groups. Charles is ahead of me with our Professional Hunter, Strangles Middleton, and I am back with the trackers and ranger. We made our way up and down the river looking over the pods and searching for older bulls. I had elected to leave my rifle in the gun rack on the truck as I was not hunting. It would be a decision I would later wish I hadn’t made. It’s like insurance; you don’t need it till you need it.

Strang selected two bulls from each of the pods, and we walked the river listening to the hippos grunting and watching them surface out of the water, growing more irritated with our presence. Hearing a hippo at that distance is an experience you won’t forget. The memory of going to sleep each night and being awakened each morning to the sounds of hippos in the river is one my African memories that I shall always cherish. We set up on one pod, but the hippos ended up moving further away from us before our group could get settled in and wait for a shot. We moved out and returned to sit on the other pod. They were equally as thrilled with us being there.

The African hippo has the distinct honor of killing more people than any other animal on the continent , and while they may appear slow and clumsy, they can reach speeds of nearly 20 miles an hour on land. Hippos spend the majority of their time in the water, but will often leave the safety of lakes and rivers to feed on land at night. They may travel as far as ten miles away during these nightly feedings. You do not want to find yourself between a hippo and the water when it’s trying to return as the outcome could become most unpleasant. We settled in at a distance that did not disturb them too much, and Charles readies Strang’s .375 H&H on the sticks. The wait is on. We were seated in the sand about ten yards from the water’s edge. Hippos were in the river about fifty yards.

It felt like we waited hours on the bull, but in reality, it was only about 90 mins. There were multiple times Charles almost took the shot only to have the bull change position or another hippo moved and block his shot. It was a welcome relief when he finally pulled the trigger, as the African sun was starting to bake us a bit on the river bed.

Strang said it was a good shot, and as we started to make our way down the river, red in the water confirmed what Strang had said. I was walking behind one of the trackers with Strang and Charles in the lead. Suddenly the tracker stopped and yelled “hippo bwana” and pointed. As I turned to my right, a hippo was about 40 yards away from us, running in the direction of our right flank and towards the river. My first thought was “How did Charles’ hippo get on land?” We had not taken our eyes off the river, and none of us saw the hippo come out of the water. I thought it was Charles’ hippo because as he ran and chomped at the air with his teeth, the slobber looked for a moment like blood. I quickly realized it was impossible for that to be the same hippo, and this was another very irritated one. Strang told all of us to freeze and not move as he and Charles brought rifles to their shoulders.

The hippo stopped directly in front of us about 40 yards away. Strang repeated his commands to us, and the tone in his voice reminded us all just how serious this moment really was. A hippo on land can be a very dangerous animal to deal with, and especially one that is trying to return to the safety of the river! I want to say I wondered why I did not have my rifle with me, but honestly that thought would come later. In the moment I was confident in Strang’s ability with his double and Charles with the .375H&H, but like the insurance I mentioned before, you don’t think about it until your house has burned down or you have been in an auto accident. Looking back now, I wish I had had my rifle just in case.

The hippo was biting the air and looking at us. At this moment, he had a choice to either charge the group or move another 5 yards into the water. The standoff felt like it lasted an eternity, but really was only 5-10 seconds. We stood frozen and the hippo started to relax first putting one foot into the river and then the other, and with that we slowly started to back up. The hippo ignored us and moved on as our backward steps became quicker. When we reached a safe point, we turned around and discussed what we had just experienced. Strang said he had no idea why the hippo did not charge as all the signs of a possible charge were there. He was biting the air and looking at us with the same look Ruark described about a Cape Buffalo that looked at you as if you owed him money. But, for whatever reason, the hippo decided to not bother with us and went on with the rest of his day.

A fisherman walked up to our group and said he watched the whole scene unfold. He saw the hippo come out of the bushes on the bank . Apparently it was there sleeping and the shot woke him up and he was making haste for the river. When asked why he did not alert us about the hippo, he said he thought we saw it, so there’s that! We made it back to the truck and I replayed the morning’s events over in my mind. I sat there and just let it sink in. This was my first morning in Africa, my first safari, and I was in one of the last truly wild parts of the continent. had dreamed of Africa most of my life, and the writings of Peter Capstick pulled me to the Valley for my first trip. I was now here, and it was as wild and as beautiful as I hoped it would be.

We returned to camp for some food and to give Charles’ hippo time to float to the surface to be retrieved. We returned later and a few local fishermen had attached lines to the hippo, and with the use of a canoe, had floated him over to the bank and the process of getting him on land could start. It took several men to pull the hippo up and out over the river where it was possible for Charles to look his hippo over.

Charles got into position for a few quick photos, but we did not have long. The red ants were on the move after and we had to be very mindful of where we stepped. A fire would later be built, and an ash barrier would allow the skinners to work without the ants bothering them. An eventful first day in the Luangwa Valley was coming to a close, and we drank a couple cold Mosi lagers on the river bank to toast the hunt.

Michael Maynor

I am a proud native of North Carolina with a deep love for the sporting lifestyle and everything Southern. My book collection seems to grow endlessly, and I have a particular fondness for collecting vintage duck decoys. Despite appearing content, my heart longs to return to Africa for another safari adventure. John 3:16

You May Also Like

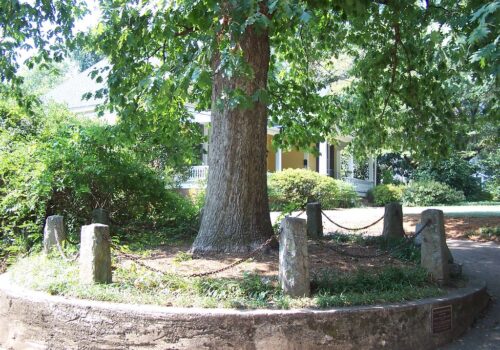

The Tree That Owns Itself

January 18, 2024

Under Kilimanjaro

November 10, 2021