From Seed to Market: North Carolina Tobacco Memories

By Boyce Maynor

With me, it is a common occurrence to see something that sends my mind back to days gone by. That happened to me recently while paying for gas. While standing in line, I saw a sign in a convenience store that was advertising a pack of cigarettes for $7.20. My mind immediately raced back to my younger days, in the early 1960s, when anyone, young or old, could walk up to a vending machine and buy them for $0.25.

Here in Robeson County, North Carolina, the saying was “Tobacco is King”. Every farmer had a tobacco allotment and every farmer raised tobacco. My grandfather was no different. Unlike today, farmers only farmed what their family could take care of. My grandfather had about 5 acres of tendable land. He and his mule would start early in the morning and work until late afternoon, if necessary.

As a young boy, many days when I was not in school, I would be at his home working for him. Whether it was hoeing cotton, plowing corn, killing hogs or milking goats, there was always a chore I could be doing. But the most labor-intensive and time-consuming was working in tobacco. That was a crop that literally required year-round attention.

I remember how he found a place on the edge of the woods to clear, that would serve as his tobacco bed for the next few years. In January, after clearing the area, he would plow through it just to rip up any unseen roots and loosen the soil. When he was satisfied that it was ready, he would prepare to sterilize the bed. He never let me help him “gas” the beds because he would use Methyl Bromide gas to kill everything (bugs and weed seeds) in the bed.

In a month or so after gassing, he would get ready to seed the beds. The beds were about 8 feet wide and about 50 to 75 feet long. I remember the seeds were so small that he would mix them in sand to add volume before hand sowing them. After sowing, he would take young bamboo reeds and make arched shape hoops over the bed to support the plastic bed coverings. After stretching the bed cover, we would use shovels to pile dirt on the edges, all the way around to seal the bed. When it was finished, it resembled a little greenhouse.

It would take a few months for the seedlings to reach the size needed for transplanting. Just before the plants were ready, he would get the rows prepared for the plants. A typical tobacco field would be laid out with four rows ridged and skip one, then four more rows and skip one. Following this pattern for the entire field. The skipped row served as the “crate row”. This is where the mule-drawn tobacco crate would stay beside the croppers so they could load it with tobacco leaves.

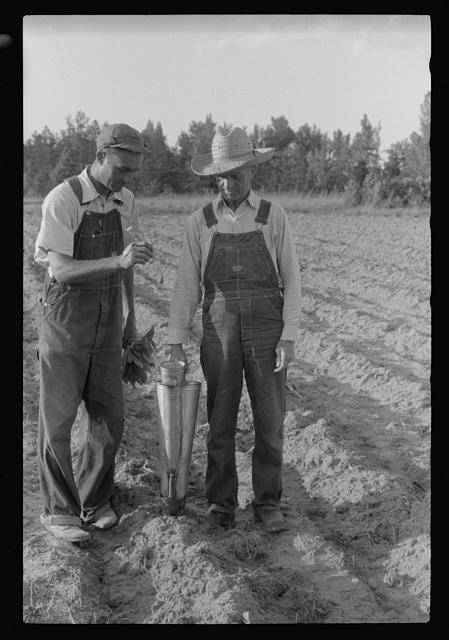

When transplanting time came, we would go to the beds and pull plants. My grandfather used a hand transplanter. As he would stick the end in the soil, the person “dropping“ plants would place a small plant in the top of the transplanter. Then, he would pull a handle to allow the plant and a small amount of water to fall into the hole the transplanter had made. Using your foot, the dirt would be packed around the plant. Transplanting usually required three or four people to make it go smoothly. One to use the transplanter, one to drop plants and one or two to supply water and plants to them.

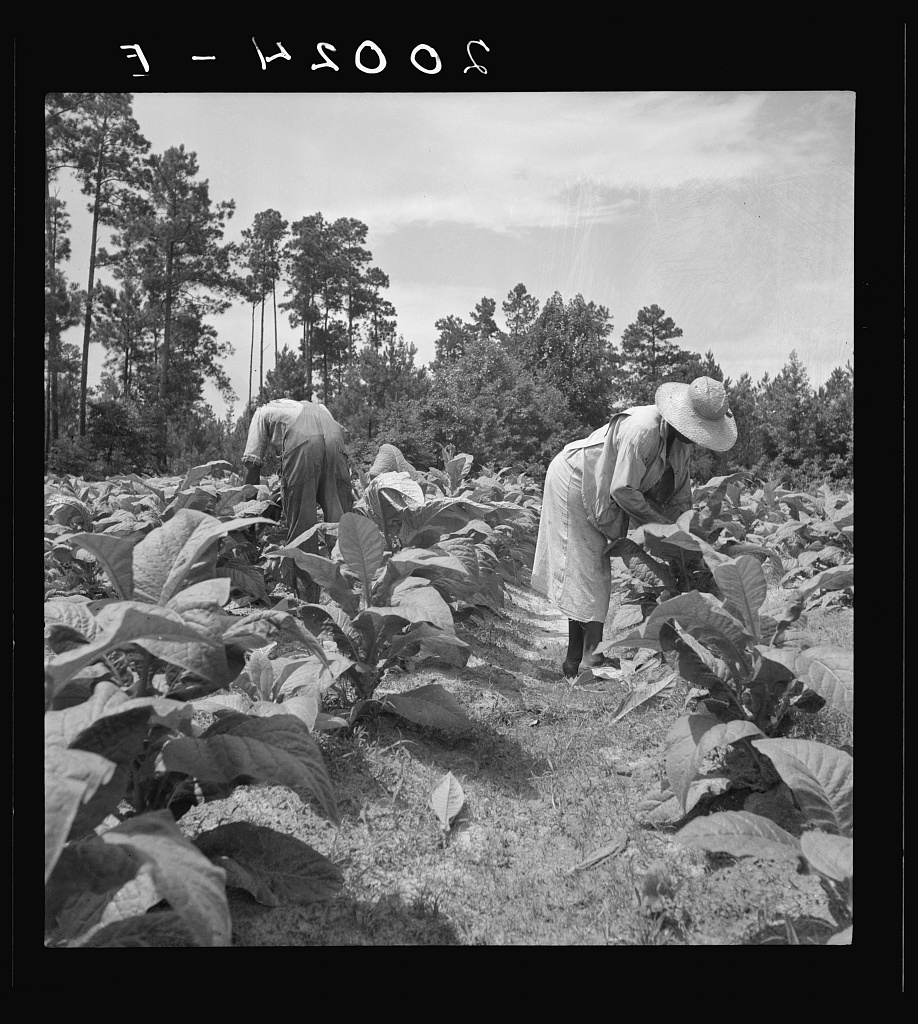

After the plants began to grow, we had to keep them free from weeds and worms. We would plow the field to kill weeds and dust the plants with worm poison to control pests. As the plants grew, suckers would develop where the leaf attached to the stalk. “Suckering” tobacco was a labor-intensive job. Each stalk of tobacco may have suckers at every leaf. You would have to break each sucker off. It wouldn’t be long until your hands were coated with the sticky goo from the suckers.

As you go through the field you would also look for any plants that had started producing a flowering bud in the very top of the plant. This bud, if left to grow, would flower and produce seeds. Breaking these buds was known as “topping”. Removing the flowering part of the plant allowed all the energy to go to the leaves. When the plants had grown to maturity, the very bottom leaves would begin to yellow (Late July to early August). This was the signal that harvesting was at hand.

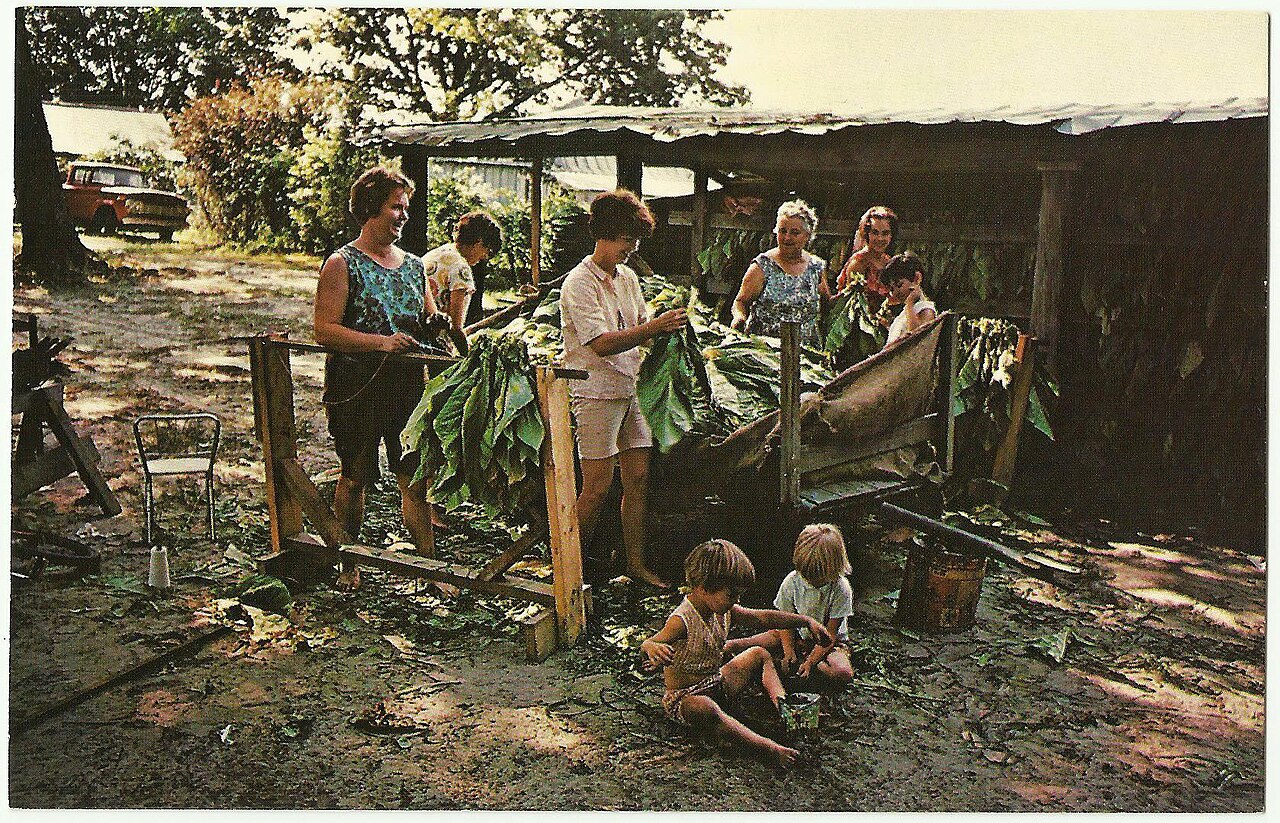

Since there were so many farmers growing tobacco, those that used the same workers, would pick different days to “put in” tobacco. I remember I would be at Mr. Solomon’s on Tuesday, Mr. Merlin’s on Thursday and my grandfather’s on Friday. The scene around the barn was similar from farm to farm. There would be four people in the field cropping the turning leaves, one or two people driving the mule-drawn tobacco crates, two or three women at the barn stringing and two people per stringer handing three leaves at the time to the stringers.

I was never able to master the art of stringing tobacco. A tobacco stick was 1 inch by 1 inch by 5 feet long. The stick would be placed in a holder that held it about chest high. Tobacco twine would be secured to the end next to the holder and the stringing would begin. Depending on the stem thickness, the handers would give the stringer 2 to 3 leaves. From one side to the other, the stringer would take the leaves and wrap the twine around the end of the stems. Back and forth, back and forth, the process continued till the leaves were tied to about 8 inches from the end of the stick. When the stick was full. It was placed in a pile near the barn door.

Out in the field, the croppers were finishing the field four rows at a time. Most times, the cropper would just sling the leaves under his arm until he had all he could hold. Then he would go to the crate row and lay the armful of leaves in the crate. But not my grandfather’s tobacco. He demanded that you would spoon each leaf on top of your arm to prevent any stems being broken. When you placed the leaves in the crate they would be in perfect order. He always believed that broken stems affected the curing.

After all the tobacco was cropped for that day, the croppers would go to the barn to begin hanging it in the barn. The typical tobacco barn was about 25 X 25 feet and about 25 feet high. The interior was a series of parallel, horizontal boards spaced so that each end of the sticks would rest on the tiers. The tiers went from one side of the barn to the other side and from about 6 feet above the ground to the top of the walls. When we would load the barn for curing, someone would go to the top tier, and there would be others on the tiers beneath him spaced so each person could hand the loaded stick to the person above him.

From the ground to the top sticks would be passed up until the top set of tiers were loaded. Then to the second from the top till it was loaded. All the way down to the bottom tier until the barn was completely filled with green tobacco. Very early tobacco barns were heated with wood and later fuel oil was used. A large heater sat in the middle of the dirt floor, and as soon as the green tobacco was loaded, the barn was heated. Drying the tobacco, or curing as it was known, was an individual choice for each farmer. But typically, the barn would be heated for 2 days at about 130 degrees, then raise the temperature to about 155 degrees for two days and then finally to about 180 degrees for the last two days. Six days were the standard time for curing because the barn had to be opened and cooled.

The tobacco would now be brittle, and a day with the doors opened and the barn cooled allowed it to absorb some moisture from the air, which would make it pliable again. The barn had to be unloaded the next day so tobacco could be put in again. We would take the cured tobacco out of the barn and store it in a barn called the “pack house”. The tobacco in the pack house had to be taken off the sticks so that it could be graded by leaf quality.The adults grading the tobacco would look at every individual leaf and separate it by appearance and quality. After grading, the tobacco would be “tied” into small bundles. Each bundle was about 15 leaves with their stem ends together. Then a leaf was folded and wrapped a few times around the stems to hold them in a bundle. This was referred to as “tying tobacco”. After tying, the tobacco was stacked in piles on burlap sheets so it could be loaded on trucks to be taken to the market. In and upcoming article we will look at the tobacco market.

Boyce Maynor

I am from North Carolina. I retired from teaching math in 2019 and devote most of my time now to yard work, gardening and just “messing around” the house. I was raised to love hunting, fishing, and softball. I spend a lot of time, now, documenting cemeteries/burial plots and genealogy. I am the proud father of one son, that keeps me going with things to do and places to go. I also love to reminisce about days gone by.

You May Also Like

Five Quotes About Fishing

July 15, 2020

Sun, Dust & Borrego Cimarron

March 18, 2020