Hemingway’s Secret African Passion..Wingshooting

By Edgar Castillo

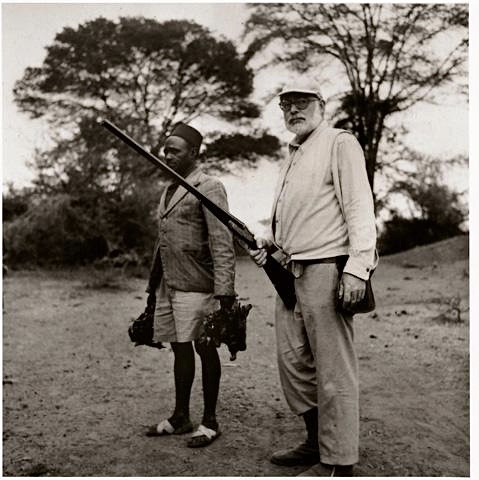

“Bwana! Bwana! Ganga Namaqua!” The swift flying birds were dive bombing the small watering hole. Ernest, who was lazily sitting against a large boulder, was busy watching giraffes slowly move through acacia trees, along with a herd of nearby grazing zebras. He had been waiting for the next wave of sandgrouse, but instantly sprang to his feet when he heard the commotion. Though time had begun to creep up on him, Ernest was still quite lively. It was hot. His light-colored garbs consisted of the quintessential safari hunting outfit. Leather boots, a well-worn sun-faded tan vest, a white poplin-collared shirt, khaki cotton pants, and a sweat-stained billed tan cap instead of a Pith Helmet rounded out his wingshooting attire. It was simple and effective for a day of bird hunting under Africa’s scorching sun

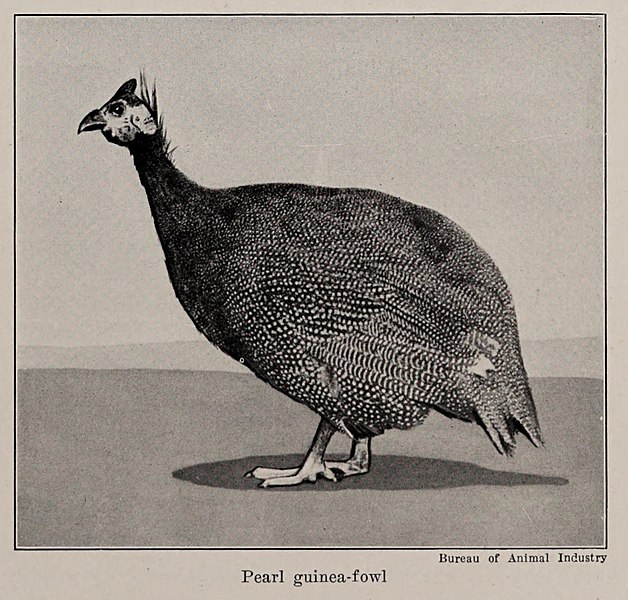

Ernest’s sudden movement did not spook the determined birds away. In Africa, every living organism requires precious water. Sometimes, the danger that awaits its prey does nothing to dissuade thirst. With his beloved side-by-side, Ernest carefully chooses one bird out of the entire flock. Both barrels emit a thunderous clap across the savannah. Two birds fall! Ernest brakes open the shotgun, and two spent cartridges are tossed to the ground. They land in the soft sandy ground, amidst large cat prints. A rifle lays within hands reach just in case. From the leather pouch strapped to his hip, he grabs a pair of shells. They are inserted quickly, and a volley of shots are fired rapidly. More sandgrouse drop from the blue sky. One of the local tribal villagers, who’s wearing a pinstriped sports coat hurriedly gathers up the birds. “Betty good, Bwana.” Ernest watches the rest of the flock fly off to the west. They’ll be more. He returns to his rocky perch and waits to be hailed again. Laying motionless at Ernest’s feet are Guinea fowl, and a tattered pair of francolins. Hyenas are heard in the distance. Their vocalized and sinister laugh are their calling card. They instinctively know that feathered carcasses will be found close to the watering hole come darkness.

Yes, the above “shoot” account is fictional. However, I am sure that a scene like what I described took place at a few watering holes or there were eyewitness accounts of Hemingway walking the scrub open country pushing small plump Galliformes to flush into the air, during his last trip to the dark continent. Hemingway knew even during his day that great bird hunting opportunities were being overlooked and overshadowed by his own big game exploits. His hunting safaris are world renowned and are frequently seen in his works. Even his love for fishing takes center stage above bird hunting. What is not well known is Hemingway’s love for wingshooting. Glimpses of his passion for the uplands can be seen in his travels to Idaho, where Hemingway loved to hunt pheasants and ducks with the likes of legendary Hollywood actor and close friend, Gary Cooper. There are scores of B&W photographs of Hemingway engaged in upland bird hunting at home, but hardly a word of his wingshooting endeavors in Africa.

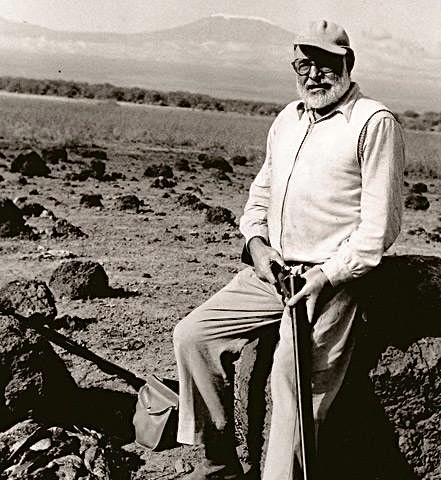

Hemingway visited Africa twice. He spent a total of ten months traveling and exploring the massive wild and dangerous Serengeti countryside. Stalks for lions and rhinos made the headlines, as well as still-images of massive horned kudus and sables at Hemingway feet are what captured his adventurous lifestyle. However, I think it was Hemingway’s silent, less publicized love of African wingshooting are what carried a subtle, yet heavy influence in some of his writings.

Hemingway penned several references and well-known quotes regarding wingshooting, particularly in his African stories. Hemingway’s 10-week safari to Kenya in 1933 provided him material and inspiration for his short stories “The Snows of Kilimanjaro”, “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” and 1935 novel “The Green Hills of Africa”.

My fictional two-paragraph introduction was inspired by Hemingway’s short single sentence description, “This was a pleasant camp under big trees against a hill, with good water, and close by, a nearby a dry water hole where sand grouse flighted in the mornings.” – The Snows of Kilimanjaro.

I have absolutely no doubt that Hemingway saw those birds every day and patterned them enough, that one mid-afternoon, he positioned himself nearby in the attempts to pass shoot some of the dove-like sandgrouse and add some flavored African poultry to the menu.

Upon retrieving the limp body, Hemingway would gaze upon the gorgeous ground dwelling bird and softly stroke its vivid markings. Male sandgrouse have a somewhat orange buff head, throat, and chest, with brown colored backs and speckled wings with white markings and pointed tail that are similar in shape and flight as American white-wing doves. In another of his famous citations which is often copied and used religiously by bird hunters everywhere… “When you have shot one bird flying you have shot all birds flying. They are all different and they fly in different ways but the sensation is the same and the last one is as good as the first.” – Fathers and Sons. What more proof do you need?

Want more evidence Ernest Hemingway was a devout and opportunistic bird hunter after my own heart while in Africa? Fans have no doubt read or at least heard of his book, “The Green Hills of Africa”. In this wonderful literary work, Hemingway describes a carefree encounter with snipe while duck hunting with his second wife, Pauline. “A flock of dark ibises, looking, with their dipped bills, like great curlews, flew over from the marsh on the side of the stream where Karl was and circled high above us before they went back into the reeds. All through the bog were snipe and black and white godwits and finally, not being able to get within range of the ducks, I began to shoot snipe to M’Cola’s great disgust.” I’m confident that Hemingway wasn’t worried about losing sleep over his actions and unimpressed gunbearer.

Hemingway more than likely used his famous W.& C. Scott & Scott 12-gauge pigeon shotgun to bring down an array of African gamebirds and waterfowl when he wasn’t face to face with leopards and cape buffalo. Hemingway was described “as fine a wingshot as ever”, and probably didn’t have much difficulty in shooting a good number of birds. He would have been exposed to the partridge-like cape francolin in the Western Cape province, and pheasant-size guinea fowl, both occurring in multiple species, as well as pea fowl, plenty variety of doves and pigeons, a smorgasbord of ducks and geese, and yes, even quail. All would have been a welcomed table fare in the Hemingway canvas tent.

I will be bold and say Hemingway may have opted to silently move through the brush gripping his shotgun instead of the Westley Richards double rifle, as local tribesman chanted to drive the small turkey-sized helmeted-guinea fowl into the still African air. With overlooking mountainous peaks swathed in clouds in the distance, the sweeping panoramas of the Serengeti would suddenly be dotted with screaming birds. In one fluid movement, Hemingway would snap the shotgun to his shoulder and fire. Lifeless bodies would fall. Nearby animals scattering at the sound of the manmade thunder. Maneaters and other dangerous game would rest easy this day, as bird hunting would take centerstage. One could only wonder.

Hemingway is described as a rumbustious man of action, a literary bullfighter in the arena and in life, a deep-sea fisherman, war hero, world traveler, and a passionate seeker of outdoor adventures. His personality was larger than life. Ernest Hemingway’s illustrious and well-documented big game safaris are legendary! His personal and fictional hunting escapades captured the minds and hearts of many, BUT I want to picture Hemingway startled at the whir of wings and marveling at the sight of exotic gamebirds flushing from jaraguá grass before he squeezed the trigger…he was an African wingshooter at heart.

Edgar Castillo

Edgar Castillo is a recently retired law enforcement officer for a large Kansas City metropolitan agency. He also served in the United States Marine Corps for twelve years. Edgar’s passion lies in the uplands as he self-documents his travels across public lands throughout Kansas hunting open fields, walking treelines, & bustin’ through plum thickets in search of wild birds. He’s a contributing writer for several publications and e-magazines/websites. Follow the author’s adventures on Instagram @hunt_birdz

You May Also Like

Where the Water Returns: Land, Heritage, and the Lumbee Legacy at Camp Island

April 21, 2025

Feathers & Whiskey Podcast: Episode 2

May 26, 2025