Grant’s Gazelle in Tanzania

By Michael Maynor

“Clean miss!” I heard the words almost instantly after I squeezed the trigger on what I would later learn was an excellent Grant’s gazelle. “The bullet went right over his back,” my Professional Hunter JP Van Wyngaard yelled as we rushed to catch up with the ram that was now moving quickly away from us. I shook my head as I looked at the shooting sticks I was using; they were not the tripod style I was use to on but were a different setup that held the rifle in more of a cradle position. This setup allowed the rifle to be a lot more stable, but it took longer to get into position and while you could move up and down quickly , sideways movement was not as easy without moving the complete system.

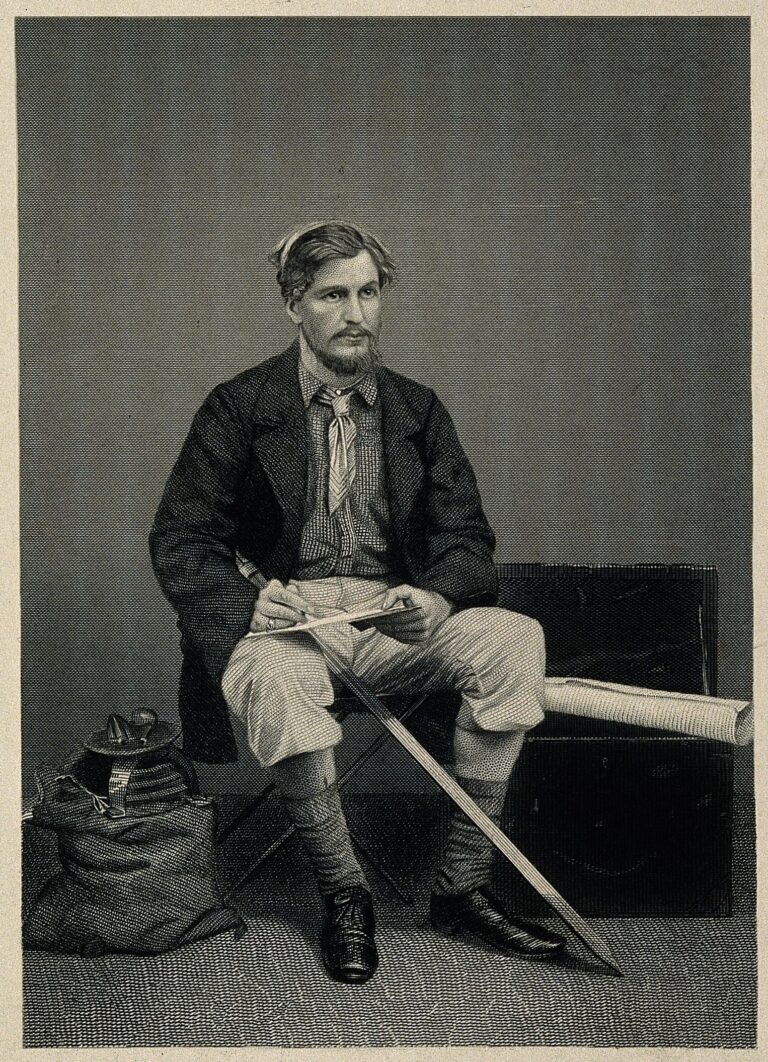

We tried to set up on him a few more times, but this old warrior knew the game and he would never let us get close again. Finally, we gave up and started the slow walk back to the truck. I felt a bit discouraged, but JP advised me he would rather have that than a wounded animal, and of course, I agreed. It really was the best outcome aside from getting my hands on him. I looked down at the Masailand dust coating our boots as we walked and decided to just put the whole business out of my mind. The Grant’s Gazelle is named after James Augustus Grant, a Scottish explorer in eastern Africa. The gazelle that carries his name can be found in Northern Tanzania, South Sudan, Ethiopia, and from the Kenya coast to lake Victoria. The Grant’s is related to the Soemmerrings gazelle and the Thomson’s gazelle.

We arrived back at the truck and climbed up, and the command was given to start driving. I settled back in the seat and took a sip of water, and gazed out across the vast, open lunar-like, landscape. The area known as Masailand stretches from Tanzania to Kenya and is home to the Masai people. The Masai are herders that keep larger herds of cattle and goats. I am sitting in my canvas tent catching up on some writing before we leave to hunt Thomson’s gazelle, and a herd of Maasai cattle have recently passed. I can still hear the faint sound of their cattle bells in the distance.

Our search for another shooter, Grant’s, takes us far from camp and across the arid plains. Since the Masai are herders and not hunters, the area around our camp is teeming with game. We see many Grants rams, but when we are searching for a proper ram we see giraffes, zebras, ostrich, gerenuk, and lesser kudu.

Before taking a break for lunch, the decision is made that we will drive to the top of a distant hill and do some glassing. The Masai refer to this hill as “ Mlimarada,” which means “ the mountain to see everything or the whole thing.” As the name suggests, it’s a vantage point used by not only the local Masai, but game rangers that are looking for potential poachers.

Once we reach the top of the hill we are greeted by a couple of Masai men and a dog resting under the shade of the only tree at the top of the hill. We spent some time glassing the land below and saw lots of Grant’s and other game taking refuge from the blazing African sun under any tree or bush that offers shade. Finally we decide that it’s time for lunch and we make our descent down the hill.

The shade of the Acacia tree was as welcoming to us as it had been for the Grant’s that darted from under its canopy as we approached . The truck is parked and the dining table is unpacked and put into position and then the lunch box is unpacked. We dined on schnitzel made from Coke’s Hartebeest and a delicious pasta salad. We rest under the shade of the tree and enjoy the cooling breeze, but soon it is time to once again take up the hunt.

We traveled miles from our camp, and as it was growing later in the day, JP made the decision to turn towards camp and continue searching. Travel in Masailand is made difficult because of the rutted roads and washouts caused by erosion from the ground being a fine powder made from the many hooves of the cattle and goats that the herders walked across it daily as they graze. There is no patch of ground that does not have hoof prints on it, and during the rainy season, the land is washed away.

We navigated the bumpy roads until we could turn onto a “hunting road” that was grated and hard packed. The power lines that sprang up broke the illusion and reminded us that the modern world was still here. The road made travel faster, and as the truck sped down it, we saw some elephants in the distance, and once again, suddenly, the truck stopped because the trackers had spotted something in the distance. It turned out to be a couple of Grant’s rams. As we looked at them through the binoculars, It was determined they were nice rams worth pursuing.

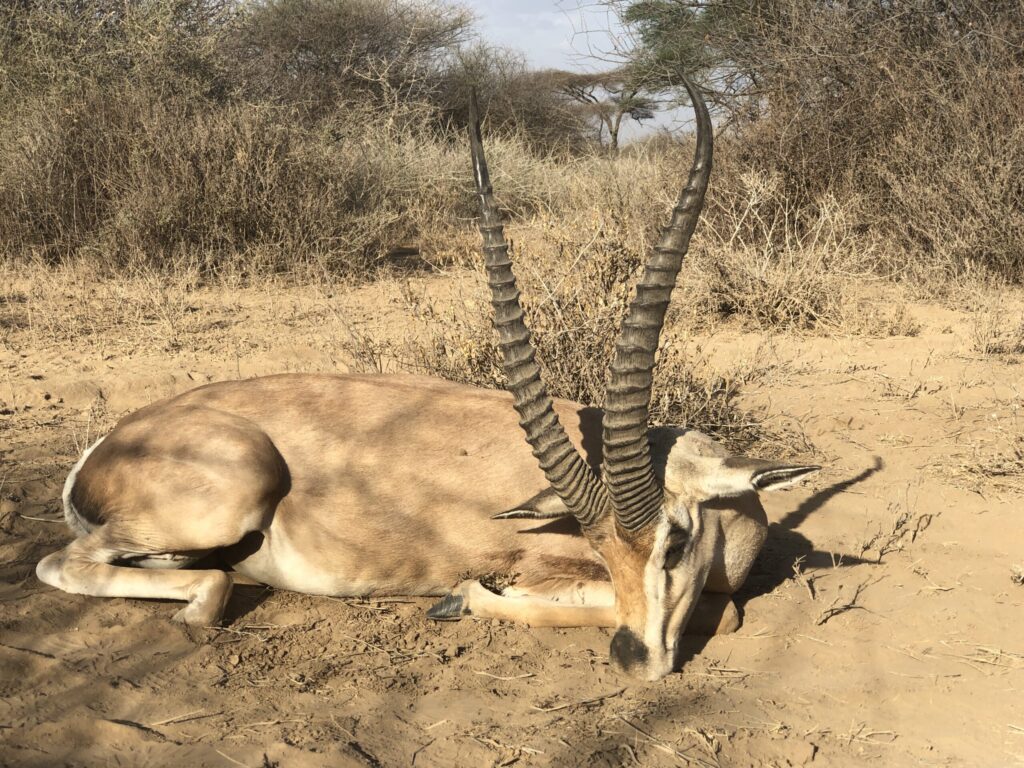

We climbed down, I chambered a round into my rifle. The stalk was on. We made our way slowly to the last location we saw the rams. We took advantage of the cover and the wind blowing in our faces and got set up on the shooting sticks. The one ram moved and presented his vitals, but I did not feel comfortable with the shot; after missing the ram earlier that day, I was not going to take a shot till I was 100% comfortable. We moved again around another bush and set up this time, the ram was broadside, and while I could not see his horns, I was confident in JP’s assessment that he was, in fact, a mature shooter. I slowly squeezed the trigger and felt the shock and surprise as the stock pushed into me. At the shot, the Grant’s turned and ran, but he did not go far. I had my Ram.

As we make our approach it’s clear this ram was not the one that had the flair to his horns, but what this ram lacked in flair he made up for in mass. I could not close my fingers around the bases of his horns. I took a few moments to reflect and to thank God for the successful hunt and clean kill. I placed my hand on the Grant’s and thanked him as well. After a few moments in reflection, it was time for handshakes and congratulations. It was then determined that the truck would not be able to get to our location, so before we hauled the Grant’s back to the truck, we moved him into better lighting for pictures as the sun was starting to go down.

After a round of photos, we carried the Grant’s to the truck and got settled in for the ride back to camp. I asked JP what direction Kilimanjaro was and he pointed behind us. I turned and looked and to my amazement, I could finally clearly see the mountain. Kilimanjaro was visible after being hidden all day by the dust and dirt that filled the air. I sat and stared at it as I felt the truck start to move, I had just taken my Grant’s gazelle in the shadow of the most iconic mountain in all of Africa.

It would be difficult to describe just how much I have wanted to set eyes upon this mountain. If you spend time reading about Africa like I do and following the trails left in books by the hunters that came before, the mountain takes on an almost mythical status Most people know it because of the short story by Ernest Hemingway The Snows of Kilimanjaro that opens with the famous line about the frozen leopard.

"Kilimanjaro is a snow-covered mountain 19,710 feet high, and is said to be the highest mountain in Africa. Its western summit is called the Masai "Ngaje Ngai," the House of God. Close to the western summit, there is the dried and frozen carcass of a leopard. No one has explained what the leopard was seeking at that altitude."

- Ernest Hemingway

As the truck bounced along the rutted roads back to camp, I watched the mountain. I wanted the image burned into my mind. I was watching as though it was the last thing I was going to see on this earth. I finally asked JP to let’s stop so I could take some photos with my camera, and as the guys talked I snapped away. I eventually tucked my camera back into its bag, and the engine fired up, and I watched again till the thick bush and dust finally blocked my view. I thought about Ruark, Hemingway, Thomson, and all of my hunter heros who had walked this land and gazed at this mountain. And now, in some way, I was connected to them all through our love of Safari and Africa and her wild lands. The times may have changed and the dark continent was no longer as dark, but Killimanjaro was still there, still standing as a silent witness to all of those that hear the siren’s song and answer her call.

We were not far from camp when we were treated to a special treat from the African bush. We saw something dart across the road, and I knew it was a hyena, but it took my mind a second to realize this hyena had a bushy tail and stripes; it was a striped hyena. The truck stopped, and we enjoyed this rare sighting. A big thanks to JP, the Trackers, and everyone who made this hunt possible!

Michael Maynor

I am a proud native of North Carolina with a deep love for the sporting lifestyle and everything Southern. My book collection seems to grow endlessly, and I have a particular fondness for collecting vintage duck decoys. Despite appearing content, my heart longs to return to Africa for another safari adventure. John 3:16

You May Also Like

Tar Heel Traditions

May 24, 2023

Questionable Medical Advice

April 3, 2023