Listen for the Whistle

By Robbie Perdue

If you want to know the health of a Southern landscape, listen for the whistle.

Not the machinery kind. Not the wind.

The thin, rising bob-WHITE that once stitched together fields, hedgerows, and pine woods across the South.

Bobwhite quail don’t survive by accident. They are not adaptable generalists. They are specialists—creatures of edge, disturbance, and restraint. Where quail live, the land is doing something right. Where they are gone, the land is usually still productive, but it has become simplified, overgrown, or overmanaged in the wrong ways.

Quail are not a nostalgia species. They are a barometer.

What Quail Require (And What the Land Must Give)

Healthy quail habitat looks messy to the untrained eye. It is a mix of bare ground and cover, seed and insect, sun and shadow. It is fallow corners and burned understory. It is broom sedge, ragweed, partridge pea, and briars allowed to exist without apology.

Fire—applied deliberately and frequently—does more for quail than any food plot ever could. So does rotational disturbance: disking, light grazing, selective thinning. Quail need ground they can move across, overhead cover they can vanish into, and insects they can catch without crossing a parking lot of pine needles.

When landscapes become “clean,” quail disappear.

The Role of the Hunter (And the Restraint It Requires)

Good quail hunting has always been more about walking than shooting. More about dogs, weather, and listening than limits.

Historically, quail thrived not because people left the land alone, but because they worked it with a light hand. Small farms, timber cuts, grazing, and fire created the mosaic quail depend on. Today, restoring quail means thinking less like a consumer and more like a caretaker.

That includes restraint.

Not every covey needs pressure. Not every bird needs to be taken. Quail populations respond best to habitat work first, harvest second.

The whistle tells you when you’ve earned the privilege.

Why Quail Matter Beyond the Bird

Manage land properly for quail, and quail are rarely the only ones to benefit.

The same early-successional habitat that sustains bobwhites supports songbirds, pollinators, rabbits, and wild turkey broods. Even deer respond to the increased browse, cover, and insect life that follow thoughtful disturbance. When quail return, they don’t come alone.

Quail country is living country.

It is land with margins, not monocultures.

It is evidence of intention.

In a time when conservation is often reduced to signage and slogans, quail demand something more practical: fire lines cut, equipment used carefully, and patience measured in seasons, not weekends.

Listening Again

Many Southern hunters remember quail the way they remember old fences or family farms—things that used to be everywhere until they weren’t. But quail are not gone. They are waiting.

Waiting for edges to return.

Waiting for fire.

Waiting for someone to listen.

If you want to know the health of a Southern landscape, listen for the whistle. And if you don’t hear it, ask yourself what the land has been asked to give—and what it hasn’t been allowed to keep.

Robbie Perdue

is a native North Carolinian who enjoys cooking, butchery, and is passionate about all things BBQ. He straddles two worlds as an IT professional and a farmer who loves heritage livestock and heirloom vegetables. His perfect day would be hunting deer, dove, or ducks then babysitting his smoker while watching the sunset over the blackwater of Lake Waccamaw.

You May Also Like

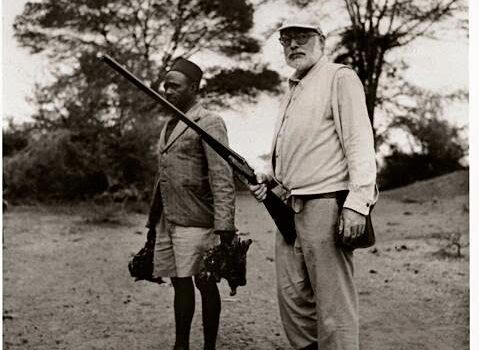

Hemingway’s Secret African Passion..Wingshooting

July 21, 2022

Commemorating 250 Years: The Birth of North Carolina’s Independence

May 21, 2025