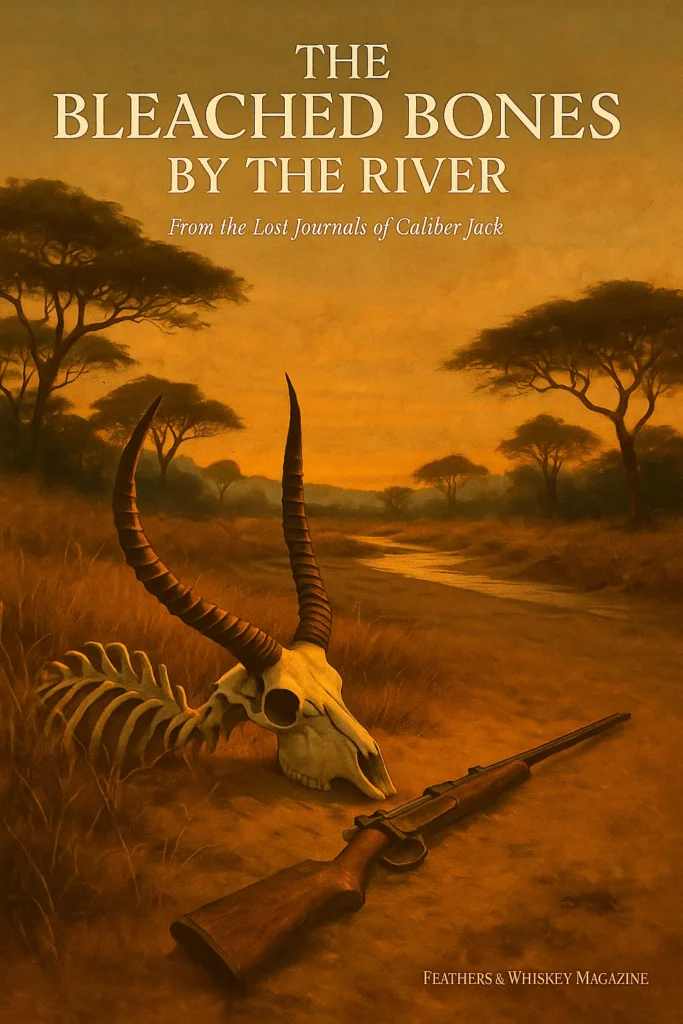

The Bleached Bones by the River

From the recovered journals of Caliber Jack

We found them in a dry riverbed east of the Ruaha — a tangle of ribs and horns half-sunk in dust, the kind of scene the wind forgets to cover.

At first I thought it was just another carcass left by poachers.

Then I saw the rifle.

And the boots.

The man had been dead a long time — long enough for the grass to grow through his belt and the insects to finish the rest. His bones were white as salt. The rifle beside him was a .375, breech still open, one spent shell stuck halfway out, the brass green with age.

Ten paces away lay a waterbuck — a great bull, heavy even in death. His horns curved backward like question marks toward heaven. One side of his skull was cracked where the bullet had struck too high.

It wasn’t hard to piece together. The man had hit the bull wrong, followed the blood trail into the brush, and walked straight into him. A wounded waterbuck doesn’t always run. Sometimes he waits. The first charge had likely driven the rifle from his hands. The second finished the argument.

Mosi kept his distance. “Bad place,” he said. He meant the kind of ground that remembers.

I crouched beside the bull, tracing the line of the horns with a finger. They were worn smooth from years of fighting — a veteran’s crown. The hunter’s knife lay broken near his boot, its blade snapped, handle dark with age. It hadn’t been a clean death for either of them.

I’ve seen worse.

I’ve seen elephants lie down beside the men who killed them, as if to apologize.

But something about this pair — the way their bones leaned toward one another — felt almost deliberate, like two old adversaries who’d reached the same conclusion.

The land doesn’t care who wins.

It just takes attendance.

Mosi asked what I’d write about it.

I told him nothing.

Some stories aren’t meant to be told until the bones are clean.

“The land keeps what it teaches.”